Artist residency serves as pilot program in state park

About three dozen people braved seasonal temperatures to hear California-based artist Monroe Isenberg explain how over the course of a week-long residency in Cape Henlopen State Park, he and patches of American beach grass were going to collaborate in artistic production.

“It’s a bit abstract,” said Isenberg.

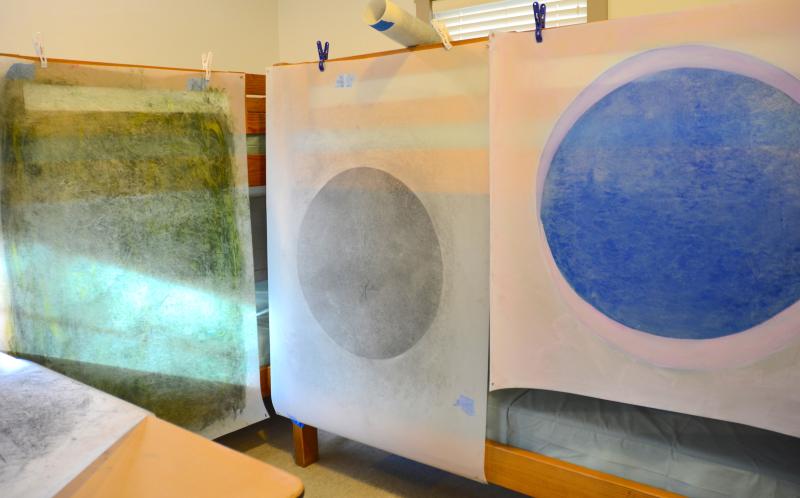

Describing it as an ecologic artwork production, Isenberg, who was one day into his residency during a walk and talk event Jan. 7, said he was using human-sized sheets of Dura-Lar as the canvas. He put holes in the corners and used twine to secure the canvas to four wooden stakes. Then he placed the canvas over patches of the beach grass, with the stakes keeping it in place. He already had two sites up – one had a fine layer of charcoal rubbed across it that the grass was going to slowly rub away; the other was over grass that Isenberg had spent four hours tying small pieces of charcoal to.

Beyond that, Isenberg was still in the figuring-things-out stage of the residency. He said he was going to play with time – minutes, hours, days of exposure to the grass – as well as color, shapes and layering. He said he didn’t know how much he wanted to participate in the production process.

“I’m creating the way for it to happen. They’re the artists,” he said.

American beach grass was chosen because it's a keystone species that creates and stabilizes, he said.

“Everything relies on the building of the dunes. If not for the grass, everything that's going on around us that’s so special wouldn’t be happening,” said Isenberg.

The project is part of an initiative called Past Present Projects, a Philadelphia-based organization that facilitates contemporary art exhibitions in partnership with historic sites. Heather Moqtaderi, Past Present Projects founder and artistic director, said it took two years to make the residency come to fruition, and it was the first time in the organization’s history that it was doing an outdoor site.

Laura Frick, exhibitions and publications coordinator for the state parks, said the project was a pilot program. It’s a new use for the park and there’s a possibility there could be more like it, she said.

Following the description of the project, the group headed out to the artwork production site, which was set up on a dune ridge off a trail near Fort Miles. Frick may be hopeful there are more residencies in the park, but before any trekking up the dune began, she reminded everyone not to go beyond the peak. Only a few people at a time could see the artwork production site. After everyone had seen the sites, Frick smoothed out the footsteps the best she could to make it look like there was no trail.

Wrapping up the event, but with days still to go in his residency, Isenberg talked about how he was still learning what the grass wanted to do and how much interference he wanted to bring to the project as a human. It’s about human and non-humans being in conversation, he said.

Isenberg stayed in a cabin at the state park as part of the residency. A couple of days after the walk and talk, Isenberg was putting his artistic touches on the canvas and getting ready to head back to California. He said he was still struggling with how much he wanted to participate in the artwork, which was why he also hadn’t decided how many pieces he was taking back to California with him and how many he was going to leave with the folks from Past Present Projects.

There’s talk of an exhibit, but the idea of working on them back at home where there’s better lighting and more time to let the pieces take shape sounds good too, said Isenberg.

“I’m squeezing about a month-long residency into a week,” he said.

Chris Flood has been working for the Cape Gazette since early 2014. He currently covers Rehoboth Beach and Henlopen Acres, but has also covered Dewey Beach and the state government. He covers environmental stories, business stories and random stories on subjects he finds interesting, and he also writes a column called Choppin’ Wood that runs every other week. He’s a graduate of the University of Maine and the Landing School of Boat Building & Design.