Crab Pot Jamboree draws attention to derelict trap dangers

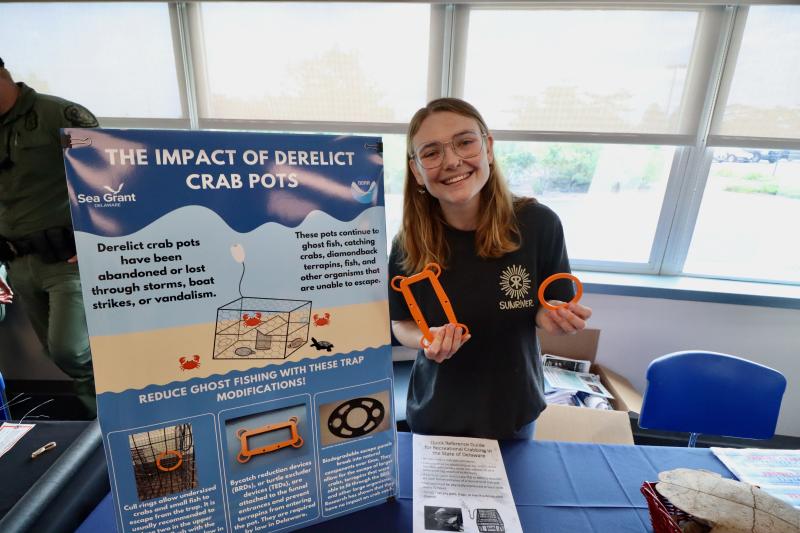

An estimated 30,000 crab pots litter the bottom of Delaware’s Inland Bays.

Those lost and abandoned pots lead to ghost fishing, where crabs, turtles and other marine animals can get stuck inside and eventually die.

“If a line gets severed or somebody just forgets to go get the trap, it’s just continuing to trap the crabs, fish and turtles. It’s trapping them forever. They’re never going to get eaten,” said Brittany Haywood, coastal ecology specialist at Delaware Sea Grant.

Delaware Sea Grant hosted a Crab Pot Jamboree Aug. 7, at the University of Delaware’s Hugh R. Sharp Campus in Lewes. The goal was to draw attention to the hazards of derelict crab pots and the impact on the state’s blue crab population.

Several government agencies and organizations were there to show how they are using technology to find the crab pots and retrieve them.

Haywood said rescuing crab pots starts with volunteers.

“Every winter, we host a roundup event. Folks in boats go out, use side-scan sonar to find them, then another team hauls them up, and we recycle the ones we can,” she said.

Haywood said they pulled up 50 pots in a single day last year. She said they have retrieved 340 pots in the last four years.

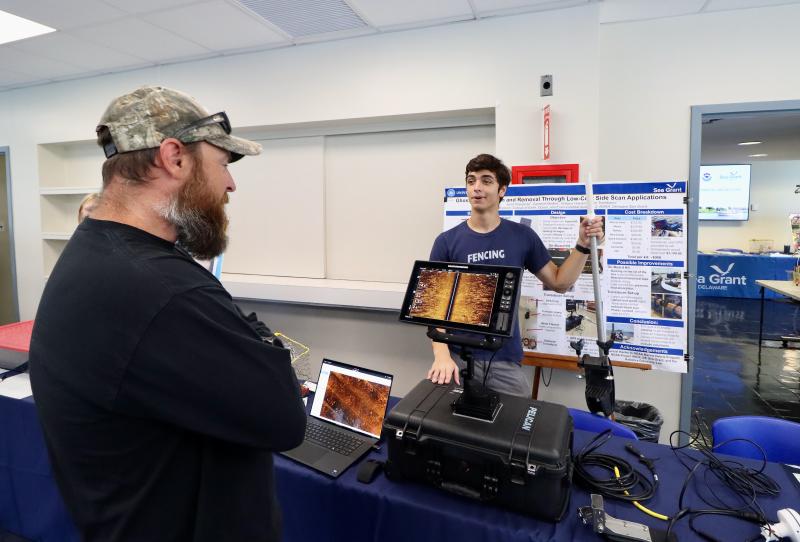

Jared Wierzbicki a University of Delaware student who works in the Center for Composite Materials, showed off the side-scan sonar at his table.

Sean Bennett, who works for DNREC’s Division of Watershed Stewardship, was eager to learn the capabilities of the high-tech tool.

“We recently got similar equipment on our boat to survey the coastline, just getting depths. But with the side-scan, we can fine tune it and find crab traps or identify stuff on the bottom. This is a new learning curve for us,” he said.

There was also an opportunity for people to learn about the best practices for safe crabbing.

Haley Cylinder of Milford left happy after getting her old pot checked out at the trap check station.

“It’s been hanging in a garage for over decade. They said it just needed a new line. I didn’t think this would be up to regulation, but it apparently is,” Cylinder said.

Ben Wasserman of the Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife displayed charts showing how the blue crab population in Delaware Bay has declined slightly over the past two years. But, he said, things are headed in the right direction.

”I think people are hopeful about crabs in Delaware Bay right now. One thing that has been hard on them, historically, is cold winters, and we’re just not seeing those like in the past,” Wasserman said.

Edward Hale, who is with the extension faculty of University of Delaware and Delaware Sea Grant, said there is no assessment of the blue crab population in the Inland Bays. But, he said, the harvest is probably pretty high with the recreational fishing community.

Hale hosted a handful of live blue crabs at his table for visitors to see and touch.

Fabrice Veron, dean of the University of Delaware’s College of Earth, Ocean and Environment, said the recreational fishers and crabbers bring more than $90 million to the Delaware economy each year, and blue crabs are an important part of the ecosystem.

He said the bipartisan infrastructure law provided funding for the crab pot project.

“We have been able to improve our community by teaching volunteers how to deal with this marine debris issue, working together with UD faculty, students and Sea Grant specialists,” Veron said.

Jamie Bavishi, deputy administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said the jamboree is an example of getting a lot of pieces to fit together.

“We’re addressing the problem [of derelict crab pots] with terrific science and also through partnerships with communities,” she said.

Project Able Bootcamp

While crabs consumed one side of campus, computer science professor Christopher Rasmussen was focused on oysters in the robotics lab.

Rasmussen and his oyster team were part of the week-long Autonomous System Bootcamp.

The summer camp for techies brought 60 students and faculty from about 30 universities to get hands-on experience with UD’s high-tech research toys.

Rasmussen said his team uses video from underwater vehicles.

“Basically driving around oyster beds, wild or farmed aquaculture, doing a census. Are they living or dead? How old are they?” Rasmussen said.

The bootcamp was part of Project Able, which stands for align, build, leverage and expand.

Project Able is a UD-led effort to advance technology and develop a workforce for the Blue Economy. It is being funding by a two-year, $1.3 million grant from NOAA.

Five different projects were underway in various parts of the UD lab and campus, according to Rob Nicholson, strategic partnerships innovation director and an oceanography officer in the U.S. Navy Reserves.

”The bootcamp is intended to be super technical and scientific and give some sort of creativity and flexibility to work on projects that aren’t driven by timeline or budgets,” Nicholson said.

Nicholson said having the bootcamp at the same time as the Crab Pot Jamboree allowed NOAA leadership to see all the projects happening on campus.

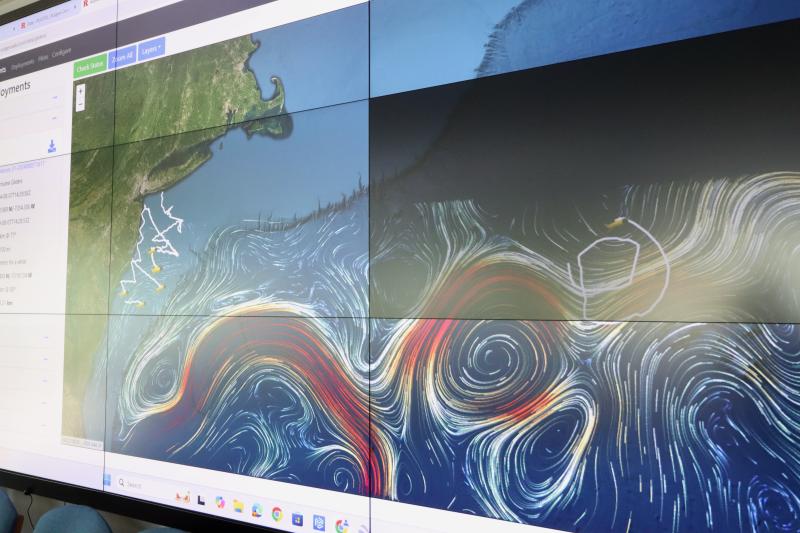

In a conference room, for example, the glider team was helping weather forecasters collect data on ocean conditions as remnants of Hurricane Debby moved up the coast.

The glider is a yellow drone that looks like a torpedo with wings.

The students put a map on a big screen that showed where the UD glider, and gliders from other universities, were in real-time off the Delaware coast.

They said the gliders were able to map changes in ocean temperature pre- and post-Debby arrival to help forecasters know if the storm was going to get stronger, weaker or stay the same.

At the same time across Pilottown Road, a handful of different torpedo-shaped micro-marine vehicles skimmed across the water at the boat basin.

“It’s about to go into a dive. So, you’ll see it go underwater then come back up,” said Michael Rock, one of the UD team members.

Rock said the sea-based bots can do acoustic mapping, measure wave height, check water quality and even listen for marine mammals.

“We have about 100 of these vehicles out there, with 20 customers, all doing something different,” Rock said.

Bill Shull has been covering Lewes for the Cape Gazette since 2023. He comes to the world of print journalism after 40 years in TV news. Bill has worked in his hometown of Philadelphia, as well as Atlanta and Washington, D.C. He came to Lewes in 2014 to help launch WRDE-TV. Bill served as WRDE’s news director for more than eight years, working in Lewes and Milton. He is a 1986 graduate of Penn State University. Bill is an avid aviation and wildlife photographer, and a big Penn State football, Eagles, Phillies and PGA Tour golf fan. Bill, his wife Jill and their rescue cat, Lucky, live in Rehoboth Beach.

.jpeg)