Danielle Furst: Born to play the piano

Of all the ways Danielle Furst’s dad Jeffrey taught her to make a living from the piano, writing and composing music is the one he held in the highest regard. “That was the ultimate,” said Furst, of composing.

Furst said she has known she wanted to make a living through music for as long as she can remember, starting with sitting on her dad’s lap as a little girl. Fortunately, her dad was able to show her how to make a living in music through composing, teaching or even selling pianos.

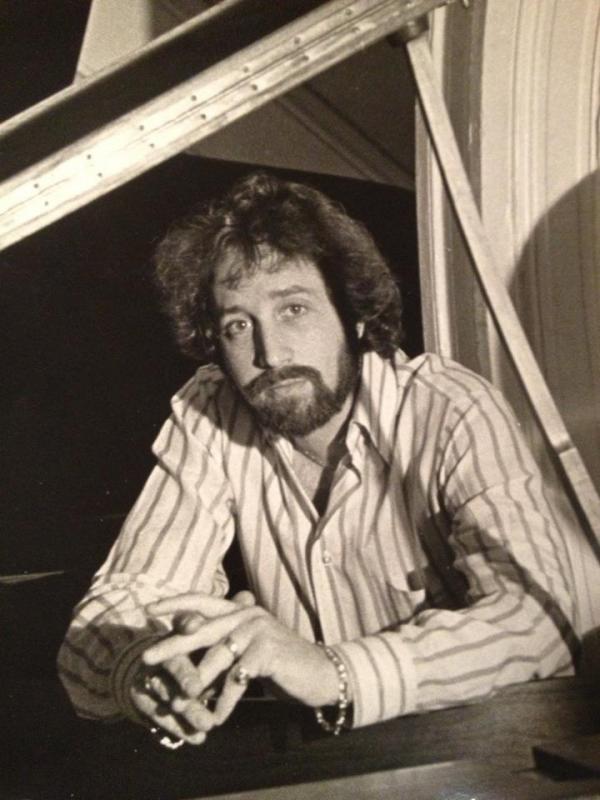

“He was an incredibly talented musician, and he gave me all the tools,” said Furst of her dad, a jazz pianist who founded a music conservatory in Boston and sold pianos. “He taught me everything.”

Furst said she was born to play the piano, and it’s always been what she wanted to do. She didn’t go to a performing arts school, but she said she soaked up everything and anything her father said. She watched him teach. She watched him sell.

“He never had to tell me to practice,” she said.

Furst started performing in her teens and then spent most of her 20s selling pianos in Miami and then London. It’s all about closing the deal, which is aided by knowing the country of production, the wood used and all the nuances between the different makes and models, she said.

Selling pianos is something Furst is good at. She said she probably could have continued to make a comfortable living doing so. Even now, she said, when she moves to a new area she introduces herself to the local sellers and teachers. “I like the action,” she said of selling a piano. “I have that skill, but luckily, I don’t have to do that right now.”

For about a decade, Furst has been making a living composing music for films and documentaries. Most recently, she composed the soundtrack to the Netflix documentary series “The Pharmacist,” about a pharmacist whose son was killed during a drug-related shooting and the father’s journey to shed light on the country's opioid epidemic.

Furst said other musicians, composers and music students have started to reach out to her because of the new series. So far, the reaction had been pretty good, she modestly admitted.

Furst credits her dad with giving her the knowledge, but she credits her brother, Jenner, with forcing her to make the commitment to being a composer. She said he basically forced her to compose the music of a movie he made right after graduating from college.

“I was full of self-doubt. I was afraid of failing,” she said. “But as soon we got done with the project, I knew composing was what I wanted to do. I felt immediately I had found my purpose – to create and share music.”

Despite being from the same family, Furst said, her brother doesn’t play music. He’s got the ability to hum a tune, but she said, she’s the one who can turn it into music. “We’ll be around the production team, he’ll hum something, and they’ll want to know if I understand what he wants,” said Furst. “I do.”

Furst said the creation process is tedious. She’ll meet with a producer, who has a crumb of an idea, and she’ll be told what the movie is about. Afterward, she said, she’ll be doing something and a melody will appear in her head. “It’ll be something I can’t shake. Then I’ll get home, work it out and record the arrangement,” she said.

As part of the production process, Furst spends weeks at a time in Los Angeles working with Grammy-nominated musician Khari Mateen. It’s a partnership that worked as soon as the two met, said Furst. “He’s my musical soulmate,” she said.

Furst said she still is surprised by the musical choices producers use in their movies. She said she’s not involved in the final production of the movies, so she ends up paying attention to the music the first time she’s seeing a completed project.

“We’ll create hundreds of hours of music, most of which doesn’t get used,” she said. “Sometimes, we’ll create something that we don’t think is even going to be used, then we’ll watch the movie, and it will be the music used as the central theme.”

For the last five years, Furst and her husband, Nathan, lived in a yurt on his family’s farm in Georgetown. During that time, she said, her baby grand piano was in her in-laws’ house. The yurt served its purpose, but there’s no comparison between playing an electric keyboard and a real piano, she said.

“It’s a full-body experience,” said Furst.

The couple recently moved to a neighborhood off Route 1, outside Lewes. It’s much different than a yurt, said Furst. It was time to move on, she said.

Among the many advantages the new home offers, said Furst, is the ability to have her piano for her immediate use. “The piano is immediately inspiring,” she said. “It’s where my ideas come from.”

The house is mostly moved into, but Furst and her husband are still trying to figure out the acoustics of the high-ceilinged living room where they placed the piano. She said the sound bounces all over the different surfaces. A small rug has been placed underneath the piano to dampen the noise, and, Furst said, she thinks her husband is going to install sound boards. She said one of the first things she did was wail on the keys with the windows closed with her husband outside to see how loud it was.

“The music bounces off everything, and it really changes the sound,” said Furst. “It fills the whole house, but he said it wasn’t too bad outside, so I kept hammering.”

Furst said her husband never asks her to stop playing. “If anything,” she said laughing, “he complains that I don’t play enough for him. He’s always telling me, ‘You don’t play enough for me anymore.’”

Chris Flood has been working for the Cape Gazette since early 2014. He currently covers Rehoboth Beach and Henlopen Acres, but has also covered Dewey Beach and the state government. He covers environmental stories, business stories and random stories on subjects he finds interesting, and he also writes a column called Choppin’ Wood that runs every other week. Additionally, Flood moonlights as the company’s circulation manager, which primarily means fixing boxes that are jammed with coins during daylight hours, but sometimes means delivering papers in the middle of the night. He’s a graduate of the University of Maine and the Landing School of Boat Building & Design.