Raymond Sproul: Approaching 100 and sharp as a tack

Raymond Sproul was 16 years old when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. He remembers it well.

“I was at the Century Theatre watching a ‘Tarzan’ picture, and it came on the screen that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. They closed the theater down, and I went right around the corner into the post office and joined the Navy,” he said from his home west of Fenwick Island.

He was only 16, but he passed all the tests and they gave him a paper for his parents to sign. He couldn’t start until he was 17, he said, but he belonged to the Navy and the Army couldn’t touch him.

As soon as he turned 17, off he went to boot camp.

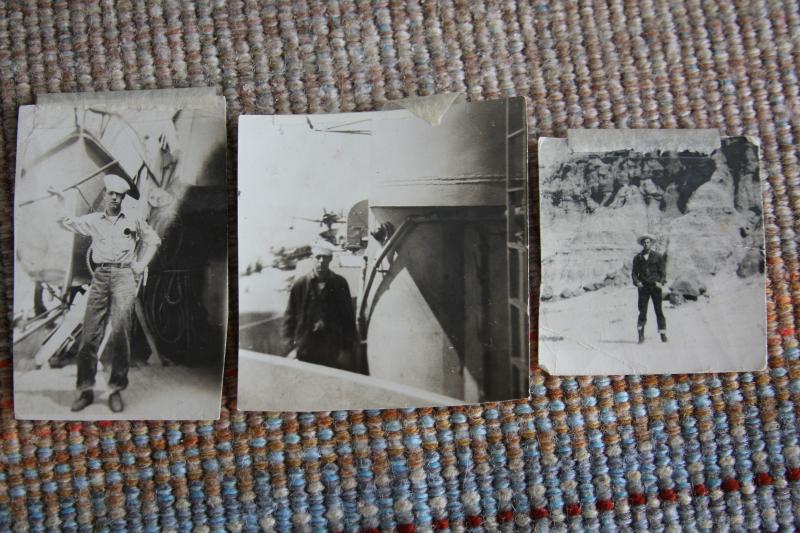

He ended up on an anti-submarine ship, known as a sub chaser, and served as a gunner’s mate first class, maintaining the ship’s guns.

“Our main job was to keep the submarines away from the merchant ships,” Sproul said.

He said he saw a lot of German U-boats, and the ship took a lot of shots, but never got an affirmative hit.

The 110-foot ship accompanied merchant ships from the Caribbean on up to Russia – an ally of the U.S. at that time – and ran into some rough seas. But as a teenager, Sproul said, he thought nothing of it.

“I was 18 and never been away from home,” he said. “You’re trained to the point that you do everything automatically, and you think nothing of it. You have no concept of what you’re doing or when you’re doing it. I was too young to be scared.”

And he learned to cope. He describes a time when he was in the ship’s crow’s nest, the highest point on deck, during rough seas that tossed the ship onto its side.

“You keep saying, ‘She’s never going to come back this time, she’s never going to come back. But she does. I could reach over and get a handful of water,” he said.

Lying in bed at 2 a.m. and getting the call to man your stations, he admits, did cause some anxiety, and looking back, he said with a smile and a twinkle in his eye that if they asked him to do it again, he’d say, “Are you out of your damn mind?”

He got out of the Navy in 1945 when the war ended, and was part of the group celebrating in New York City when the iconic kissing photo was snapped.

He then returned to Baltimore, but after a month of hanging out on the street corner, he thought what’s next?

“I tried to put up with this daggone civilian life. Then one day I decided I can’t go on like this,” he said.

So he reupped and was assigned to the battleship Iowa, cruising the Pacific Ocean and adjoining seas. The ship was massive – 2,700 men on board, compared to the 27 who were on the sub chaser.

Cruising under the Golden Gate Bridge near San Francisco, Sproul said he climbed the ship’s highest peak to try and touch the bridge, when a video caught him in the act.

“My parents got a kick out of seeing that,” he chuckled. “It was on the newsreel and my parents went to the movie theater five or six times to see the same movie so they could see me hanging out and pointing at the bridge.”

Still sharp as a tack, Sproul remembers just about every detail of his long life – even the name of the doctor when he was born in Baltimore and the hospital’s address. A month-long road trip in an old ‘41 Chevy that he took with his aunt and some friends from California to Baltimore is one of his favorite memories.

“We had a time. We stopped every place,” he said.

Even though he never graduated from high school, a captain on a ship in Key West made sure he did. Sproul got his high school diploma at sea, and also some college credits.

When he got out of the Navy, he worked for several companies as a mechanic until coming to Delaware in 1968 working for one company, and staying for another. An offer of home, job, free gas was all it took to hook him.

“I said, you’ve hired yourself a mechanic,” he said.

There were nothing but empty lots in Ocean Pines, Md., at the time, he said, and his new company put all the canals and bulkheads in the development.

“The greatest move in my life was coming to Delaware,” Sproul said.

In 1983, he bought a home in Magnolia Shores west of Fenwick Island, where he lived with his wife, Florence, who died in 2017.

“When I moved here, we were the only ones here,” he said.

He misses Florence and all his friends who have passed, but has new friends and neighbors who keep their eyes on him, and take him to errands and appointments.

“They’re the most fantastic people in the world. These ladies are always bringing me stuff,” he said.

At nearly 100, he gets around the neighborhood on a scooter, still cuts his grass with a ride-on mower, and does his cooking and housework.

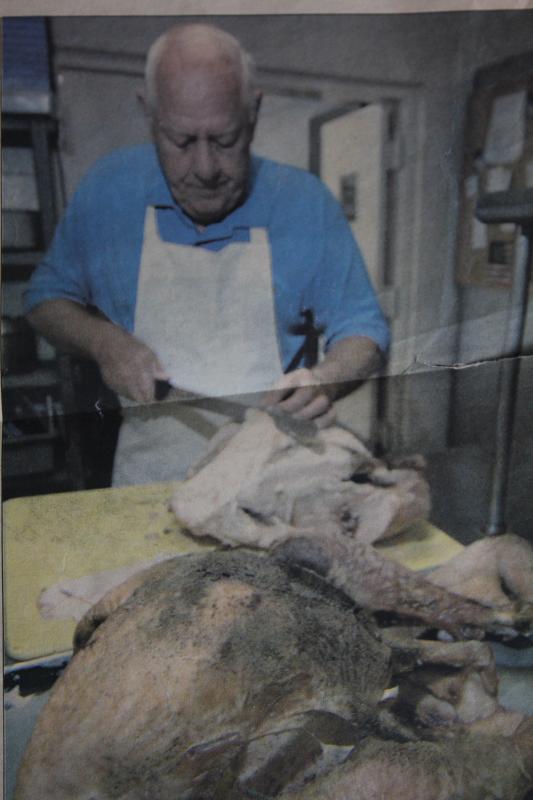

He used to boat and fish on nearby Dirickson Creek, and worked for 10 years cutting turkey at Warren’s Station restaurant in Fenwick Island.

Lately, he has taken up banjo lessons – an homage to his mother who gave him money for lessons when he was 10, but he spent the money on movies instead.

“Now I’m taking lessons so when I get to the other side I can tell my mom, ‘Look, I can play the banjo,’” he chuckles.

That sense of humor has guided him throughout life. It came out recently after a doctor appointment when the receptionist asked him about scheduling for next year, and he joked that at his age he may not be around. They made the appointment anyway.

He teases his niece and nephews about making them what they are today. Niece Pat Uroda shoots back good-naturedly, “I need my boots.”

Sproul is thankful for having lived a good life, and amazed that he can remember it all.

His family is thankful too. They’re planning a big shindig in July when Sproul turns 100. He can’t wait to see his family that includes dozens of nieces and nephews, and their children and grandchildren.

“They’re my life,” he said. “I’m not a religious person, but there’s got to be something that’s led me this far to be in a place like this.”

Melissa Steele is a staff writer covering the state Legislature, government and police. Her newspaper career spans more than 30 years and includes working for the Delaware State News, Burlington County Times, The News Journal, Dover Post and Milford Beacon before coming to the Cape Gazette in 2012. Her work has received numerous awards, most notably a Pulitzer Prize-adjudicated investigative piece, and a runner-up for the MDDC James S. Keat Freedom of Information Award.