When a product is known to be deadly, most people get as far away from it as possible.

Except when the product is heroin.

When addicts hear about a batch that's good enough to kill, that's the product they want, says Ocean View Police Chief Ken McLaughlin.

If you or someone you know is struggling with addiction or substance abuse, go to helpisherede.com or call 800-345-6785.

“There is nothing nonviolent about this heroin epidemic,” McLaughlin said.

Garry Tuggle, special agent in charge at the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency Philadelphia Division, agrees.

“We're seeing, in some cases, the fentanyl-laced heroin being marketed as such and packaged on the street so you can differentiate from regular heroin,” Tuggle said. “Unfortunately, what we're finding is that as people are dying from fentanyl-laced heroin, we're seeing other users flock to that brand.”

Fentanyl, a synthetic painkiller estimated to be up to 100 times more potent than morphine and used primarily with cancer patients, has been on the rise, state officials say. In some cases, heroin is cut with fentanyl to increase potency.

A local addict who has been trying to get clean for months says in Sussex County, if the drug he buys is packaged in blue, it's everyday heroin. But if it comes in a white bag, it's laced with something stronger, and it's most likely fentanyl.

Because it's so powerful, it's heroin in white bags that addicts want. Even if it's likely to kill.

The local addict, who asked not to be identified, fits the description of the typical heroin user: white, male, 18 to 34.

He began using while living in Baltimore. He now works enough locally to feed his habit and pay his rent.

He's one of many local heroin users who say they want to get clean, but who have weak support systems and little access to treatment. He says he feels that by being labeled as an addict, it's easier to find more drugs than to find help. As an addict, he says, it's difficult to feel connected to anything other than the drug and his dealers.

“I'm making excuses to do it,” he admits. “I don't want to go through the withdrawal.”

Meanwhile, for $65, he can score a bundle – a package of 13 bags of heroin that usually contains less than a gram of the drug.

That's about $5 a bag – cheaper than a pack of brand-name cigarettes.

Many times, addicts don't know exactly what they're getting, which may be why Delaware consistently ranks in the top 10 states nationwide for high overdose death rates.

The addict said the price and purity of the heroin in Delaware is poor compared to what he could find in Baltimore, but he keeps buying.

In 2015, purity levels in Delaware's heroin supply dropped to about 63.4 percent, DEA spokesman Patrick Trainor said, a significant decline from the 80 percent to 90 percent purity levels seen a decade ago.

But as long as the demand is there, the product will continue to sell.

“If the market demands, if they can get away with selling 60 to 65 percent pure at the street level and still make the revenue they want to make, they'll do that,” Tuggle said. “But if you took that same product and put it in northeast Philly, it wouldn't sell very well.”

Tuggle said it's impossible to talk about the heroin epidemic without discussing prescription opioids.

“In my lifetime, I've seen three major drug epidemics,” Tuggle said, noting a rise in heroin use during the Vietnam War and the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s. “The third, this epidemic we're seeing now, dwarfs the two prior epidemics. It has a feeder system the other two didn't have: misuse of prescription opioids.”

Tuggle said it hasn't always been the case, but it's now clear to state and federal law enforcement that Wilmington has the highest distribution levels of the synthetic opioid oxy – Oxycontin or oxycodone – in the country. It's four times higher than the national average – with Sussex County less than 90 miles away. And that only counts legally prescribed opioids.

“There's something happening there that has to be addressed,” he said. Tuggle said nearly 80 percent of heroin users report first abusing prescription pills, a problem that can begin in a doctor's office or relative's medicine cabinet.

The DEA has been cracking down on medical practitioners who overprescribe opioids for more than a decade in an attempt to curb the heroin epidemic's feeder system. But since 2009, only 19 DEA registrations have been revoked. Those doctors can no longer write prescriptions for controlled substances, but the revocation does not bar them from practicing medicine. All 19 license removals were on an administrative level; none included criminal investigations for illegal drug sales, Trainor said. He declined to release the names of the doctors or the practices.

But cracking down on pills has not reduced drug dependence. When pills are harder to get or become too expensive, heavy prescription drug users switch to heroin, and the stronger, the better. In Sussex, it's easy to get and cheap.

The local addict has several sources he can call and knows he can find what he needs in Rehoboth Beach, Long Neck, Lewes, Ocean View or Milton.

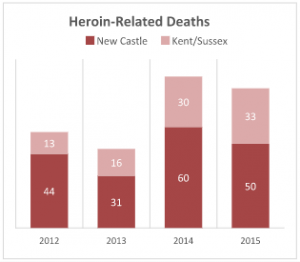

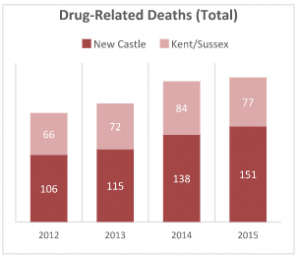

He's been lucky with his use so far, but hundreds of other addicts in Delaware have not. In the past four years, 277 Delawareans have died from heroin-related overdoses. Overdose fatalities, including everything from alcohol to heroin, have increased by 32 percent since 2012, with 228 overdose deaths in 2015 alone.

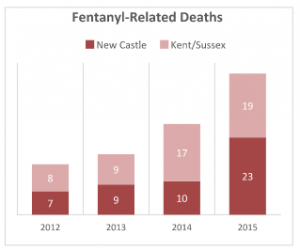

Statewide deaths involving fentanyl have jumped from 16 in 2012 to 42 in 2015.

“It's truly the worst drug epidemic that the country has ever faced,” Tuggle said. “At the end of the day, we're dying at a rate of over 120 people a day [nationwide] from drug abuse. If we were in a war zone, that would be considered mass causalities and heads would roll.”

A life-saving last resort

With a sharp rise of fentanyl-related deaths, Ocean View Police Department Chief Kenneth McLaughlin said he's surprised that the Ocean View Police Department is the only law enforcement agency in Sussex County carrying naloxone, a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose if administered in time.

“It is an absolute lifesaver,” McLaughlin said. “I'm perplexed as to why more law enforcement agencies aren't carrying it.”

All Delaware paramedics carry naloxone, but at the beginning of 2016, only a few police agencies were trained to administer it: Ocean View, Middletown, New Castle County, Elsmere, Newark and Smyrna. Harrington and Georgetown police departments say they are in the process of getting naloxone in the hands of officers.

Delaware State Police troopers do not carry naloxone, said spokesman Sgt. Richard Bratz, who declined to explain why. He said state police may be exploring a pilot program in the future.

McLaughlin said he fought for his officers to be trained to administer naloxone after responding to an overdose a few years ago.

Ocean View police arrived first on a scene where they found a familiar local man unconscious with a needle still in his arm. Police immediately began CPR and other lifesaving techniques, but when paramedics arrived less than 10 minutes later – with naloxone – they could not revive him.

“We found ourselves standing there with our hands in our pockets. They were doing CPR, but without naloxone, it's pointless,” McLaughlin said. “It was too late. We're not going to have that happen again.”

In February 2016, the state received its second donation of 2,000 cartons of naloxone from Kaléo, a Virginia company that manufactures the auto-injector kits. Kits will be distributed to school nurses in high schools, first responders, treatment centers and the state's syringe exchange program.

Each carton costs about $490, a press release stated.

In 2014, Delaware paramedics administered naloxone 1,244 times and revived 668 people, the Division of Public Health reported. The Ocean View Police Department reported two successful saves in 2015.