HMS DeBraak is ill-fated at sea and at salvage

The most famous shipwreck off the shores of Cape Henlopen in 90 feet of water is the HMS DeBraak, which sank in a terrible squall May 25, 1798. Its salvage some 180 years later attracted international attention. And because its handling was so slipshod, a new federal law was enacted to protect wreck sites.

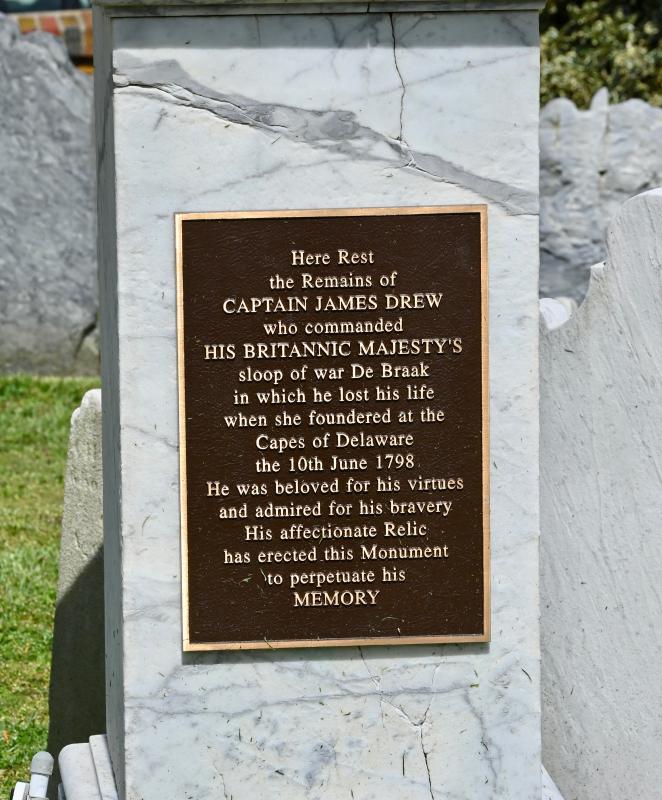

Perhaps the unknown story of the sinking is the life of Capt. James Drew, who has been portrayed as a scoundrel whose naval career includes quests to line his own pockets. He's also portrayed as a brave naval man with many virtues. He's buried in St. Peter's Episcopal Church cemetery with a plaque containing the date June 10, 1798. I'm thinking that may be the date of his burial, not the date of the ship sinking.

DeBraak was escort for a small fleet of merchant ships crossing the Atlantic.

During that ill-fated crossing, Capt. Drew left the merchant ships and captured a Spanish ship, the Dom Francisco Xavier, in the Caribbean; it was supposedly loaded with sterling silver. He returned to the flotilla and within days was victim of the sinking of his ship.

When divers searched for the DeBraak, they were able to identify the ship thanks to his inscribed ring.

The captain was among the 35 sailors and 12 Spanish prisoners (the actual numbers of the victims are not agreed on by everyone and could be as high as 46 sailors) who went down with the ship. Accounts claim that 30 sailors swam to safety, including two captured Spanish sailors who floated ashore on a barrel, which is part of the artifacts recovered. The DeBraak crew and the Spanish sailors allegedly paid for their lodging and food in Lewes with gold. Hence, the legend of riches was born.

No riches of that kind were found, but tens of thousands of artifacts were recovered. Most are stored in a Dover warehouse under the auspices of the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs, which has also coordinated untold hours of research on the DeBraak.

The DeBraak (Dutch for beagle) also has a colorful history. Built in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, in 1781, it had the unfortunate fate to be in a British port and was seized after 14 years’ service to its native country. The Brits were on a mission to take as many Dutch ships as possible because of their support for the French during the French Revolution War.

It was overhauled and fitted with a second mast and 16 guns, and was turned into a small warship. Capt. Drew was named commander of the ship and immediately complained that the second mast made the ship top-heavy. That may have been one of the crucial factors leading to it sinking 17 years later.

That fateful day of the sinking

When the DeBraak arrived at the mouth of Delaware Bay, Capt. Andrew Allen, a bay and river pilot, boarded. He sensed bad weather on the horizon and ordered the crew to take down the sails. Capt. Drew, who reportedly had been drinking to celebrate his capture of the Spanish ship, emerged from his cabin and rescinded the order. That decision probably led to the ship being knocked on its side and sinking. It went down within minutes.

When the squall hit, the crew had no time to make preparations and the open hatches filled with seawater, leading to the capsizing.

Allen was able to swim to shore and survived the sinking.

In the summer of 1798, the Brits tried and failed to raise the ship. The same fate met more than 30 other attempts to salvage the ship.

Then in 1984, the company Sub-Sal, based in Reno, Nev., appeared on the scene. Using side-scan sonar, they located the DeBraak. That news became an international sensation.

Along with the captain's ring, divers also brought up a cannon, a ship's bell and an anchor.

That set off a salvage effort that uncovered numerous 18th century shipboard items such as cannonballs, footwear, and even a toothbrush and top hat in near-perfect condition. However, according to state archeologists and historians, divers were looking for treasure (which they never found) and disposed of everything they deemed of no value, including human remains.

Before the salvage, the ship was a near-perfect, untouched time capsule of 18th century Royal Navy maritime life.

On Aug. 11, 1986, Sub-Sal went on a mission to raise the ship using a wooden and steel cradle. Unfortunately, the ship tilted during the lift, and hundreds of artifacts sank once again in the waters off Cape Henlopen.

Because of that, in 1987, Congress passed the Abandoned Shipwreck Act giving states the authority to claim and manage shipwrecks on state submerged lands.

After Sub-Sal went bankrupt, a New Hampshire investment group sold a recovered piece of hull and more than 20,000 artifacts to the state for $300,000.

Since then, staffers from the division have been documenting, cataloging, researching and analyzing the artifacts with assistance from archaeologists, scholars and historians around the world.

The hull, which is housed in a warehouse at Cape Henlopen State Park, receives four baths per day to keep the wood from drying out. The division's goal is to stabilize the hull and prepare it for permanent conservation to be displayed with other artifacts in a maritime museum. So far, no project has surfaced.

Several artifacts are on display at the Zwaanendael Museum in downtown Lewes. That's where tours originate each June, July and August following the history of the DeBraak.

A memorial near the graves of two lost sailors was unveiled on the museum grounds in 1998 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the sinking. Then, on Memorial Day 2017, reenactors laid a wreath at the grave of Capt. Drew and marched through town to the memorial.

DeBraak trivia

“Master and Commander” movie director Peter Wier viewed the artifacts to gain further information on life aboard an 18th century British ship.

One of the prized artifacts is a citrus juice bottle, which contained liquids to guard against scurvy.

Among the 26,000 artifacts are weapons, ammunition, ship fittings, a telescope, combs, dominoes, compasses, 150 shoes, three anchors and hundreds of preserved food items.

Some reports claim the top of the DeBraak mast could be seen for several years before waves and storms took toll.