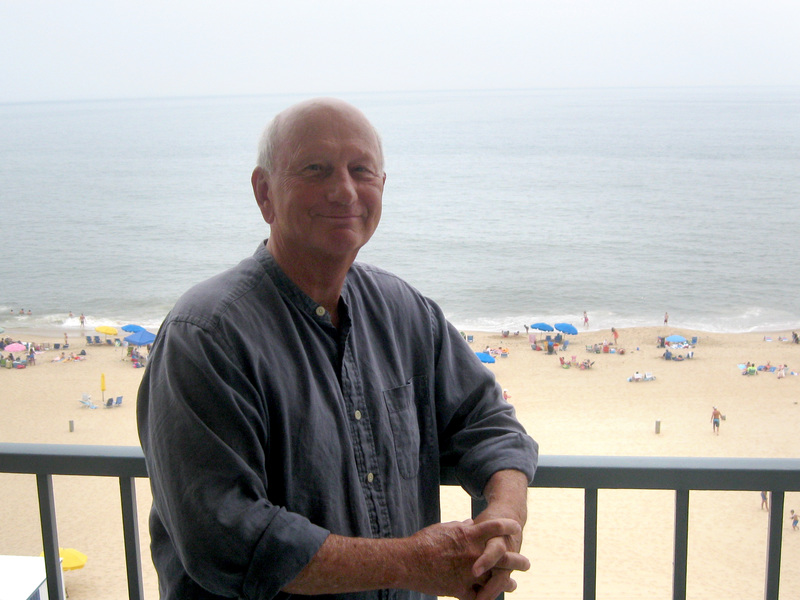

Spy on spying: author Ken Daigler

For three years, Ken Daigler woke up at 5 a.m. every day to look out at the ocean and write.

It was a long way from his 40-year career in the Central Intelligence Agency.

"I couldn’t have done that in D.C.,” he said.

The result of his work was his new book, "Spies, Patriots and Traitors: American Intelligence in the Revolutionary War."

A native of Buffalo, he does not look the part of a spy handler with his short, stocky build, bald head and dry sense of humor. His job was to recruit and manage spies. One of the first things he says is that he is bound by a secrecy oath to not discuss his work.

For the book, Daigler said, he wanted to compare and contrast intelligence work during the Revolutionary War compared to today.

“In revolutionary times, a written communication from the Culper Ring in New York would have written messages put behind a rock put on farm pasture in Long Island before it was taken across the sound to Connecticut,” he said. “Now, somebody would just attach something to an obscure website that someone else will access. It’s the same concept, just the technology has changed.”

A Vietnam veteran, Daigler said he first began researching Revolutionary War spying in the 1990s while he was still with the CIA because he was interested in how intelligence has evolved. He wrote a small pamphlet, “The Founding Fathers of American Intelligence,” under the pen name P.K. Rose, a pamphlet still available on the CIA’s website.

For the record, Daigler said, the three founding fathers of American intelligence work are George Washington for foreign intelligence, Benjamin Franklin for covert action and John Jay for counterintelligence.

Daigler’s book touches on two of the most noted spies of the Revolution: Nathan Hale and Benedict Arnold.

Hale was an intelligence officer who was captured by the British and executed, famously saying “I regret that I have but one life to give for my country.”

Daigler said much of the myth surrounding Hale is incorrect. While he was brave and dedicated to the American cause, Hale’s mission was a poorly-planned debacle; Daigler said his research indicates famous last words were likely never actually said. One problem with Hale, he said, was that in his time, Hale was a churchgoing man, raised never to tell a lie.

“As a former professional intelligence officer, let me tell you, you don’t want to send someone behind enemy lines who’s a spy who won’t tell lies. It just doesn’t work,” Daigler said with a laugh.

Arnold was the former American general whose name became a euphemism for traitor when he defected to the British. Daigler said Arnold’s handling by the British after his defection was a huge missed opportunity. He said Arnold’s knowledge could have been disastrous to the American cause; Arnold could have given the British several targets, if he had been handled better. Arnold was made a brigadier general in the British Army where he was unpopular with troops and had many of his ideas for attacks on American targets ignored by the British high command.

Daigler got into intelligence work after getting his master’s degree from Syracuse University.

“I was a case officer, and my job was very simple: I was trained to recruit assets who had access to national security information from adversaries,” he said. “It was a very disciplined life. It was very hard on the families too.”

Daigler said managing spies was always a tricky business, since people who become spies are not usually normal people; they spy for their own reasons. He said he was lucky to work with some good people during his career.

For Daigler, Rehoboth was a natural spot for retirement.

“My wife is from Rhode Island. She wanted a place where she can see the ocean. I wanted someplace that was away from international affairs,” he said.

Now that he’s retired, Daigler said, he enjoys the slower pace of life Rehoboth offers with the beach but also a sophisticated restaurant scene. He splits his time between Rehoboth, Washington, D.C., and Needham, Mass. where his daughter and her husband live.

Reflecting on his service, Daigler said, “I think people don’t realize that the point behind clandestine intelligence is to give policymakers the opportunity to solve a problem before it comes to an armed conflict.”

Daigler’s book is available at Amazon.com or from Georgetown University Press.