Broadkill Beach to widen with replenishment project

A project to deepen the Delaware Bay shipping channel is set to bring 1.9 million cubic yards of sand to Broadkill Beach. Homeowners are praising the plan, but environmentalists say dumping so much sand will damage habitats and threaten marine wildlife.

New Jersey-based contractor Weeks Marine is expected to begin work in March and will pump the sand onto a nearly three-mile stretch along Broadkill Beach from Alaska Avenue south to the border of the Beach Plum Island Nature Preserve, said U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spokesman Rich Pearsall. Weeks Marine will have until April 2016 to finish the project, which will widen Broadkill Beach by 150 feet and add an 8-foot dune.

Pearsall said he does not expect the work to run nonstop from March 2015 to April 2016 because of periodic delays due to weather conditions, but he also expects the project to be completed before the April deadline.

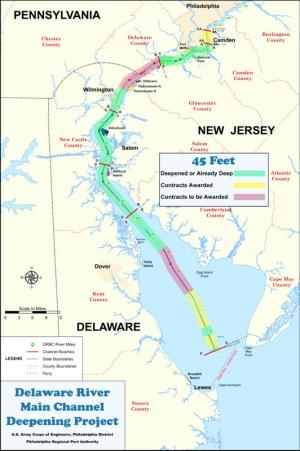

The sand to widen Broadkill Beach comes as a sideline to an ongoing Delaware River channel-deepening project that will dredge 102 miles of channel and deepen it from the current 40 feet to 45 feet to allow larger ships to navigate the bay. The total project, which is 75 percent federally funded, is expected to cost $310 million, Pearsall said. The Philadelphia Port Authority will fund the remaining 25 percent of the project.

The work at Broadkill Beach is expected to cost more than $63 million, Pearsall said.

The sand pumped onto Broadkill will come from the southernmost 15 miles of the channel-dredging project, between Bowers Beach and Broadkill Beach.

“The sand is of good quality there in that section, so it'll make good sand for the beach,” Pearsall said. “We've designed the Broadkill Beach project with the goal of maximizing protection for the community.”

He said the project is a win-win because the materials have to be deposited somewhere, and Broadkill Beach has been waiting for nourishment work since 2005.

While the widening of the beach will provide more protection to coastal homes, some environmentalists are concerned that bayshore habitats will be suffocated by the sand.

Gregg Rosner of Surfrider Foundation's Delaware Chapter said pumping sand in the spring will disrupt the yearly spring spawning of horseshoe crabs and starve shorebirds that depend on the crab eggs for food. Of special concern is the migrating red knot, which recently was recognized as a threatened species.

|

Red knot listed as threatened species The rufa red knot, which stops to feast along the Delaware Bay during a 9,300-mile northern migration, was listed as a threatened species Dec. 9. U.S. Fish and Wildlife representatives said Dec. 9 the rare red knot is threatened by climate change, sea level rise and other associated factors, making the red knot the first bird in the United States to be protected by the Endangered Species Act due to climate change effects. A decline in horseshoe crab populations, blamed on overharvesting, has been linked to the decline of the red knot, which relies on the crab eggs for fuel when it stops in Delaware each spring. By the time the red-breasted, robin-sized shorebirds arrive at the Delaware Bay they are practically emaciated, said Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control's Biodiversity Program Manager Kevin Kalasz. When the birds are ready to finish their northern journey about 10 days later, they've doubled their weight from feasting on crab eggs. "They have the fastest rate of weight gain in all the animal kingdom," he said. Since the 1980s, the red knot population has fallen by about 75 percent in key portions of its migration, which spans a round trip of more than 18,000 miles from wintering grounds on the southern tip of South America to breeding areas in the Canadian Arctic. Management plans have stabilized the crab population, and a significant decline in red knot populations has not been seen since 2003, Kalasz said. The bird still faces threats from the effects of a changing global climate system. |

He added that loggerhead turtles often chase horseshoe crabs into the bay. He said he believes the turtles also could be hurt by dredging work. Other species like oysters, clams and the lesser-known sandbuilder worm, which constructs elaborate reef-like sand structures in the Delaware Bay, could also be in danger of being suffocated by the 1.9 million cubic yards of sand.

“Putting that much sand on top of a living ecosystem sterilizes ecosystems for at least two to three years,” Rosner said. “There's a real concern for habitat loss for the red knot species, especially, because that is part of their migratory habitat.”

The endangered Atlantic sturgeon spawns in the Delaware River. Pearsall said corps biologists, Delaware's Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service thoroughly reviewed project plans and determined precautions – such as monitoring for sturgeon and turtles during dredging work – were acceptable. Pearsall said contractors will use floating pipes from the dredge to the beach to avoid disturbing sandbar shark pups.

He agreed that pumping sand onto the beach will disrupt the sandbuilder worm.

“There is a temporary impact, but there will be no lasting harmful impact to these species,” Pearsall said.

However, a 2002 study of the worms' Broadkill Beach habitats, conducted by Douglas Miller of the University of Delaware in preparation for an earlier replenishment project, concluded that the colonies would be smothered and killed by the sand during a project intended to extend the beach 200 feet from mean high water.

“While they have some capability to withstand burial under thin layers of sand, shoreline restoration would be expected to bury the present reefs at Broadkill Beach, resulting in substantial loss of this habitat,” the study concludes.

The study adds that the structures built by the worms only occur on the large rocks of artificial groins along Broadkill. The groins are structures intended to keep sand from shifting, and Pearsall said those groins most likely will be covered by sand during the planned replenishment.

According to the 2002 study, sandbuilder worm structures are unique to the Delaware Bay, with the exception of similar reef-like structures noted in North Carolina in 1970.

As for the horseshoe crabs spawning in the spring, Pearsall said the crabs will be relocated to another beach. Weeks Marine will not stop work during the spawning season, which generally runs from May through the end of June. Crabs within 1,000 feet of the placement pipeline will be relocated to completed sections behind the discharge point or to a beach location beyond the project limits.

The most recent Delaware Bay horseshoe crab spawning survey estimated 13,290 horseshoe crabs at Broadkill Beach between May and the end of June 2012.

DNREC officials could not be reached for comment about the potential environmental impacts on habitats and species such as the sandbuilder worm, horseshoe crab and red knot before press time.

Tony Pratt, administrator of the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control's Shoreline and Waterway Management Section, said the nourishment of Broadkill Beach is long overdue. He said the corps started studying Broadkill Beach in the 1980s and later identified it as a potential federal beach nourishment project because it met the criteria from the corps as a storm-damage reduction beach-nourishment project.

“It's very rewarding to see something that's been dreamed of, planned for and wished for for decades to actually come to fruition,” Pratt said. He said that the template created once the 1.9 million cubic yards of sand is placed on the beach will turn Broadkill into a project area similar to replenishment efforts at southern beaches including Lewes, Dewey Beach, Rehoboth Beach, Bethany Beach, South Bethany and Fenwick Island. Broadkill will enter into the same 50-year maintenance cycle in place at those ocean beaches.

Broadkill Beach resident Jim Bailey echoed Pratt's enthusiasm for the long-awaited project. However, Bailey, said he's skeptical of the long-term benefits of widening the currently narrow beach.

“My tenure here is 35 years, and I've seen a lot of changes. I've seen the beach come and go. We've had replenishment projects, and it ebbs and flows,” he said.

The last major replenishment project at Broadkill Beach was in 2005 when about 30,000 cubic yards of sand was dumped on the beach, Pratt said. DNREC has continued to truck in sand to patch holes, but the state agency has never undertaken such a large replenishment at this location.

Pratt said the waterline will be about 200 feet farther out into the bay than it is today.

Bailey said a widened beach will benefit the handful of homes that touch the water during high tide, but predicted that one or two large coastal storms in the future could quickly eliminate that buffer. He said he expects the project will make a significant difference in storm protection, but said he has no idea how it would hold up against another storm like Hurricane Sandy.

Bailey said about 600 people call Broadkill Beach home, and they, as well as public visitors, will benefit from a wider beach.

“There are some homes that are in peril,” he said. “We just happen to be the beneficiary of the channel-deepening project, and it's worth it by all means. The material has to go somewhere, and we're just delighted to have it.”