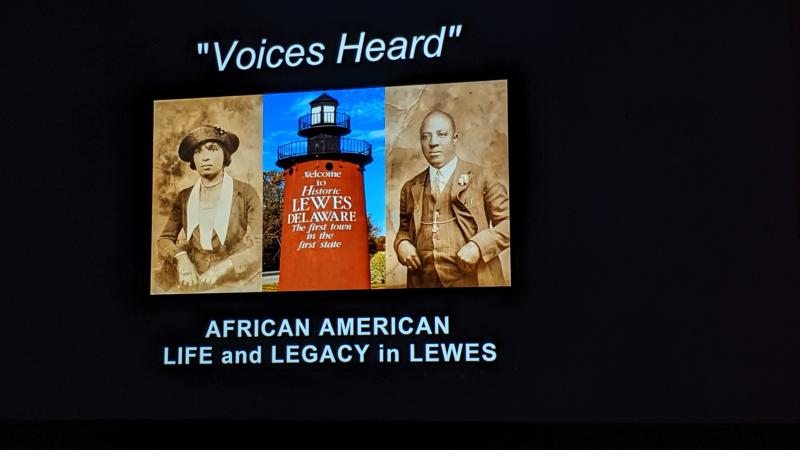

Documentary highlights Black history of Lewes

The Lewes Historical Society has produced its second documentary focusing on the history of African Americans in Lewes, and a unique tragedy during the filming exemplifies the importance of capturing the stories before they are gone.

“Voices Heard: African American Life and Legacy in Lewes Part II” continues the LHS and Lewes African American community’s attempt to preserve history that was often neglected and rarely recorded. The films feature historical photographs accompanied by testimonials from former and current residents who experienced a much different Lewes from what exists today. Ironically, Lewes was a much more diverse community during the time of segregation than it is now. While Black people had to adhere to the unjust practices, there were jobs available, and thanks in large part to Otis Smith, those jobs paid enough to afford a mortgage.

Smith told banks that refused to give loans to Black people that he would pay them enough to afford timely payments. Smith owned a menhaden fish factory and fishery located at what is now the Cape May-Lewes Ferry terminal. At one time, his operation helped make Lewes the largest fishing port in the country. Like many Black families seeking work, Lewes African American Heritage Commission Chair the Rev. George Edwards arrived in Lewes from the South with his family to work at the fish factory. Edwards, who leads Friendship Baptist Church, and his family found themselves in a community without a Baptist church, a denomination more prevalent in the South. Smith noticed that his workers were missing a major part of their life and constructed a Baptist church on the fish factory campus. Following the collapse of the menhaden fishing industry, due in large part to unsustainable practices, Smith allowed the Baptist church to take possession of the building, so long as it could be relocated. It was moved to 500 W. Fourth St.

In addition to constructing a church for his Baptist employees, Smith mandated his white and Black workers eat lunches together and rejected any type of segregation. His desire to include African Americans eventually led to his purchase of what was once known as The Field. Smith did not charge the Black community to use The Field, only asking that they use it.

To say they obliged would be an understatement, as The Field became a gathering spot for the African American community in Lewes. There was a baseball field on site, as well as open space for picnics and other leisure activities. It was the final location of the Jack and Jill Parade route. Lewes African American Heritage Commission member and Cape Henlopen School District board member Bill Collick has fond memories of the community gathering and playing in the area that is now known as Shipcarpenter Square.

Ironically, the area that was once the site of community, fellowship and athletic activities has now become one of the most restricted open spaces in all of Lewes. Prior to the present-day neighborhood, only one home existed in the field. The developers of Shipcarpenter Square changed that when they began relocating historic homes from across the state, many in Kent County, to the property. The Field was converted to private property and to this day, signs warn the public to keep off its grass. As the homes began to be restored, the property values in the area began to increase, effectively gentrifying an area that was once an epicenter of pride for the African American community. During the heyday of the menhaden fishing industry, it was estimated that more than 40% of the population of Lewes was African American. As Shipcarpenter Square began to take shape, the exodus of Black families in Lewes started as well. Even more recently, Black historians have connected the expansion of the historic district and the creation of a structural preservation body in Lewes with the decline of the African American population in Lewes. It is estimated that 1% to 3% of today’s population of Lewes is African American.

During the film, presenter Ebube Maduka walks the viewer through how a once-thriving population of hardworking, community-centric people has nearly vanished from Lewes. Mattie Walker-Green, the niece of the late Johnnie Walker, was someone who grew up in Lewes, but eventually had to move away. Her connection to her uncle, who owned a restaurant on the segregated beach, and her experience growing up during segregation in Lewes proved to be incredibly valuable for the film. Unfortunately, the urgency of the project to preserve African American history in Lewes was exemplified by Walker-Green’s interview. A couple of days after meeting with the film crew, Walker-Green, the last living connection to Johnnie Walker and his time owning the restaurant, died.

“This is my final chapter,” she told the film crew.

Lewes African American Heritage Commissioner Trina Brown-Hicks played a vital role in gathering interview subjects, as well as conducting interviews. Growing up in Lewes and residing along DuPont Avenue, Brown-Hicks is an administrator for the Facebook page Memories of Lewes and is passionate about preserving Black history in Lewes. She said interviews like the one with Walker-Green can get very emotional – both happy and sad.

“We have only just begun,” Brown-Hicks said following the screening.

LHS Director of Education J. Marcos Salaverria worked with Brown-Hicks and 302 Stories Inc. on the documentary. He said the film will be accompanied by an exhibit guide featuring 124 never-before-seen photos when it is eventually shown in schools. There are plans to air the film three additional times before the end of 2023, and segments will be posted at historiclewes.org.

Charlotte King, founder of Southern Delaware Alliance for Racial Justice, said she believes it is the type of film that should be shown in schools.

“The movie I saw today was a positive statement. It’s about a time when there was community and shared community.”

King continued, “Nobody had an attitude in any of those interviews, [even] though they went through decades of segregation and decades of only having a sixth-grade education in Lewes before being forced to continue elsewhere. Despite all of that, they spoke of a good childhood.”

She said she hopes schools will allow documentaries like this, that focus on unbiased facts and use firsthand accounts, to be shown as part of not just Black history, but also American history.

“This is the start of a community, and the continuation of history,” Salaverria said to the audience after the film.