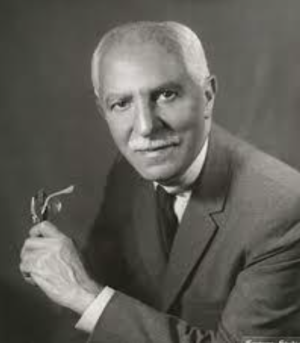

H. Albert Young’s ‘Herculean task’ in the Delaware companion case to Brown v. Board

“It seems I have a Herculean task to perform in attempting to add to what has already been presented in some eight hours of argument before this court.” - H. Albert Young, Dec. 11, 1952.

The Delaware attorney general voiced those words during the early round of Supreme Court oral arguments in Brown v. Board of Education. Young played an important yet changing role in the history of racial justice in his state – a role that transformed his own thinking and helped to transform life for all Delawareans.

For many, life is a changing journey. That certainly was true of Young; he first changed his name and then his beliefs. He was born in Kiev, Russia, May 28, 1904. His birth name was Hyman Albert Yanowitz. To avoid anti-Semitic riots in Kiev, Hyman and his parents fled the country. As with other Jews at the time, his family ended up in Brooklyn, N.Y.

His parents moved to Delaware during his early teens. He attended the old Wilmington High School at Delaware Avenue and Adams Street. He then went to Delaware College at the University of Delaware. After that, he enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, from which he graduated in 1929. While there, one of his professors convinced him to change his name to H. Albert Young – his nickname was “HY,” which stuck over time. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, he appeared in court frequently, arguing in both criminal and civil cases. He also served briefly as legislative counsel in the state houses. In 1951, he became Delaware’s attorney general – Young was the first Jew to win a statewide election in Delaware.

Defense of the status quo

To get a sense of Young’s early approach to the desegregation problem as reflected in the K-12 cases of Belton v. Gebhart and Bulah v. Gebhart, consider what he argued before Chancellor Collins Seitz at the trial level in those cases:

“The state contends, your honor, that the issue joined in this case poses a problem which requires hope and faith, character and patience. We must grow up to it. We cannot by judicial fiat impose upon a people against their will what they have accepted by heritage, tradition and governmental sanction as reflected in our constitution and the statute books for many years.”

Translated: Racial justice had to come gradually, locally and guided by state legislative norms. Hence, the judiciary should stay out of this conflict. Even so, Young had to reconcile that view with the law as announced by the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which permitted segregated public facilities as long as they were separate but equal. On that score, Young’s arguments paled in comparison to the opposing ones tendered by NAACP lawyers Louis Redding and Jack Greenberg. Judge Seitz ruled against Young on behalf of the state. The Delaware Supreme Court affirmed that judgment Aug. 28, 1952. Young tried again, asking the state justices for more time to correct educational equalities. Request denied. That left only one option: appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. Delaware did; Young filed his petition Nov. 13, 1952.

There was an irony in appealing the case. On one hand, Delaware was the only state seeking review in which segregation in public schools was declared unconstitutional. On the other hand, the Delaware attorney general joined the attorneys general of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia and the District of Columbia in arguing that such segregation was constitutional. Young, nonetheless, petitioned the high court to allow the Delaware case to be decided apart from the four other cases. Again, request denied.

During his arguments, Young urged the federal justices to do what he had asked Delaware justices to do – delay. Hence, the separate but equal doctrine was to be understood as postponing the equality side of the Plessy mandate. Young thus advocated his long stride forward principle – this some 90 years after Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Yet again, he lost; the vote in Brown v. Board (1954) was 9-0. Now, the matter returned to Delaware to implement the court’s ruling.

Paving a path away from the past

Bryant W. Bowles, a 34-year-old grifter with a racist resolve, hoped that Young might be an ally in his counteroffensive to implementing Brown’s desegregation mandate in Delaware. His group, the National Association for the Advancement of White People, strove to defeat or destabilize the desegregation order. His well-orchestrated plan was to resist Gov. J. Caleb Boggs’ post-Brown desegregation efforts. As Bowles’ oppositional efforts and school boycott campaigns garnered momentum, his cash coffers also filled up.

But Bowles had an unexpected foe. Young opposed his racist resistance campaign. Thus, Oct. 8, 1954, Delaware’s attorney general moved to revoke the NAAWP charter for its fraudulent practices. Young also accused Bowles and the NAAWP of attempting “by means of mass hysteria, mob rule, boycott and dissemination of race prejudice,” not only to intimidate Black families and school officials but also to encourage white parents to violate school attendance laws. Bowles countered by telling his followers that Young was working with “Communist Jews” to ignite racial strife. Young would have none of it. Shortly thereafter, Bowles was arrested. He was taken into custody and arraigned in Kent and Sussex courts. Of course, strife continued, but change was in the air.

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. counseled years later, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” In time, Hyman Albert Young learned that lesson ... and thankfully so!