History hides in plain sight at Cape Henlopen State Park

The annual Delaware Defense Day event at Fort Miles in Cape Henlopen State Park highlighted the Cape Region’s role in protecting the nation during World War II.

But after all the reenactors and period vehicles left, much of the not-so-obvious history remains behind in the form of foundations or repurposed buildings.

The park’s critical location at the mouth of Delaware Bay has made it a popular place for military operations and research from the Revolutionary War through the Cold War.

“The same strategic location that makes it a great spot to put a fort in World War II means it was a great spot for a Navy headquarters during World War I, for a quarantine station in the 1800s, for a couple of cannons during the Spanish-American War, a cannon during the American Revolution,” said Kaitlyn Dykes, interpretive program manager with the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. “This pincher with access to the bay has always been a really important strategic location.”

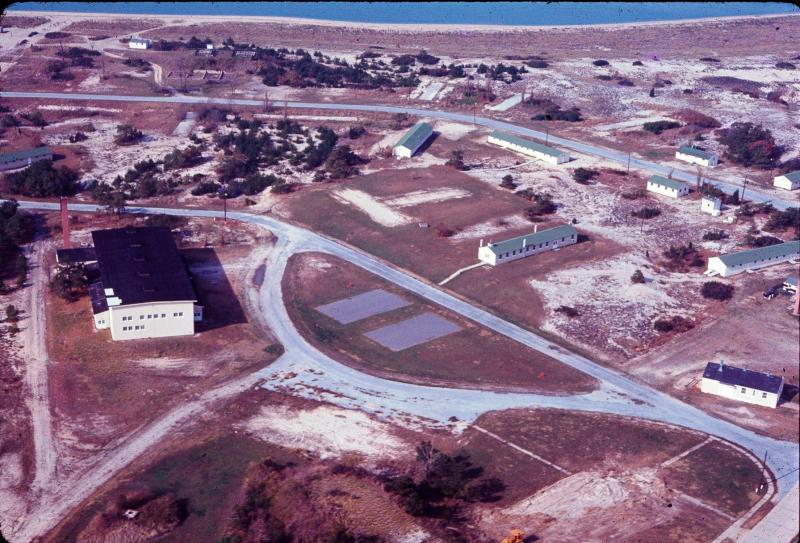

The park and everything in it is now the responsibility of DNREC. Dykes estimates there are probably more than 40 historic structures left in the park, ranging from rubble and remnants to buildings that have been renovated for reuse. Not all structures have a great story and are worthy of restoration, but their existence illustrates what once was in Lewes.

“Not to say they don’t have historical significance, but they were like a storage building or a water pump station or something,” Dykes said. “And they’re not things that necessarily lend themselves to a whole lot of interpretation.”

World War II

Outside the interpretive areas of Fort Miles, many pieces of the former military installation are either still in use or consist of foundations left over and mostly reclaimed by Mother Nature. The Seaside Nature Center, home to a touch tank, several fish tanks and other interactive exhibits, was once the prison for Fort Miles. When German soldiers were captured in Delaware Bay in 1945, they were briefly held there. However, Dykes said, the prison was only intended for misbehaving residents of the base, so the German soldiers were quickly taken north to Fort DuPont.

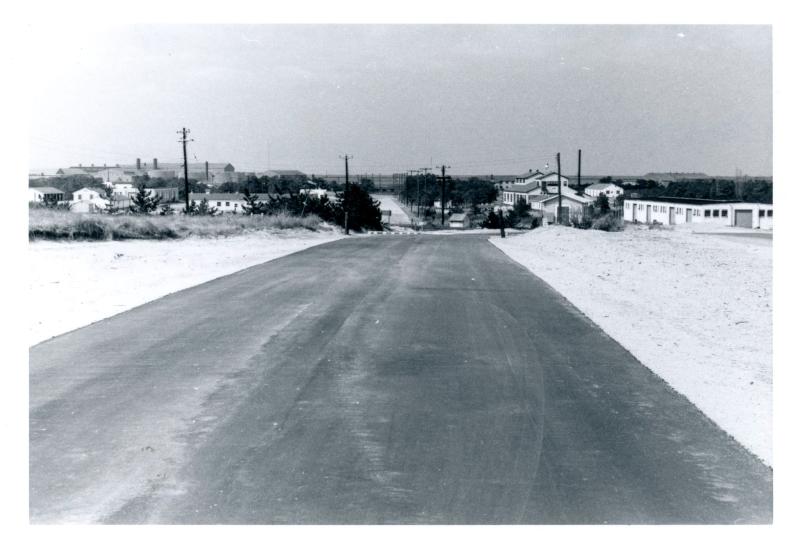

All of the youth camp buildings were used as barracks at Fort Miles. Dykes said soldiers were typically housed as close to their jobs as possible. While many of those former barracks buildings remain, there were many more, including several along the road leading up to The Point.

Moving toward the Point, the officer’s club name remains, but the building is primarily used for administrative purposes today. It’s also home to many fundraisers held by the Friends of Cape Henlopen State Park. The concrete road in front of the officers club, as well as those in other areas of the park, dates back to the Fort Miles era. One of Dykes’ favorite fun facts about the road is that the section near the officers club has dog paw prints from a pooch that wandered through the wet concrete after it was laid.

“We would never build a concrete road with no base on sand,” said Division of Parks and Recreation Operations Section Administrator Grant Melville, laughing. “A lot of the infrastructure here is still original.”

The Point has a prime example of history hiding in plain sight. The Pilots Association for the Bay and River Delaware works cooperatively with the Philadelphia Maritime Exchange in a station built atop a former World War II fire control tower at the Point. The structure is one of seven fire control towers in the park. The purpose of the station is to relay information from vessels operating in Delaware Bay to the Ports of Philadelphia Maritime Exchange.

The station was previously used by the Army, Navy and Coast Guard.

The state park’s playground and basketball court area was once the social hub of Fort Miles. It was home to a large gymnasium where basketball games and boxing matches were held. It had a theater, and a bowling alley stood nearby, about where the playground equipment is today. The area also had a chapel, which still sits atop a small hill overlooking the basketball courts. Crosses still protrude prominently from the exterior of the building. It’s the only building remaining from that complex and is now used for summer day camps.

“They tried to accommodate as many faiths as they could,” Dykes said. “For some people, that meant going into the chapel. For others, it meant mass out on the lawn. They tried to offer different things.”

Mine-building operation

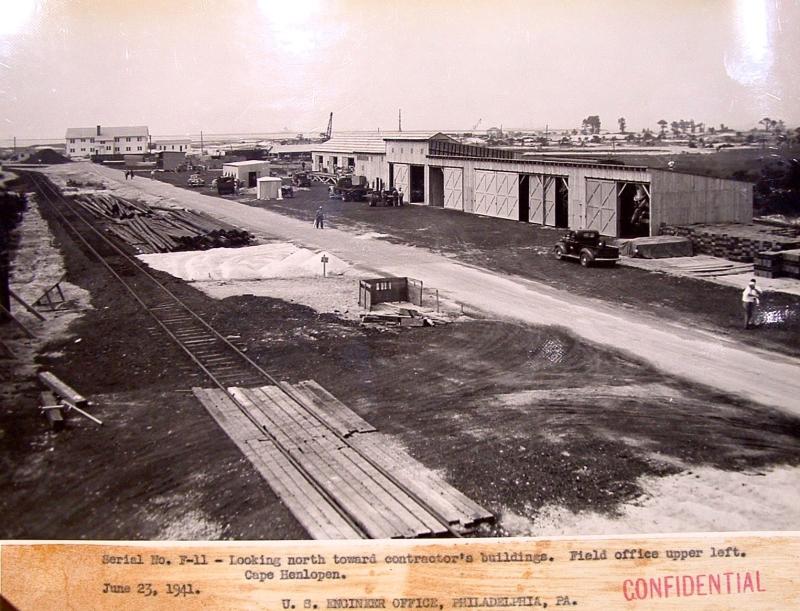

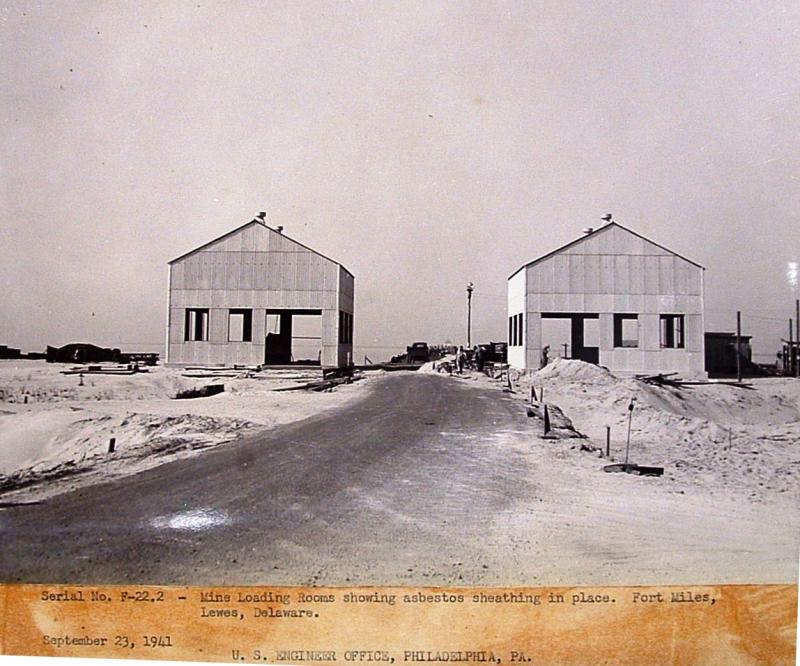

The fishing pier was the site of Fort Miles’ mine-building operation. A very large warehouse building that stored the mines still stands today. For many years, it was used by the University of Delaware. It was called the Wave Building because UD had a wave pool inside to study the movement of waves. Since UD moved out, the building is partially occupied by the Natural Resources Police.

Just a few hundred feet toward the pier are the foundations of two buildings related to the mine-building operation. One was a mine-loading room.

“The mines didn’t come with explosives in them for safety reasons, so they had a storehouse, like a warehouse for the mines, then a loading room where they’d be loaded with explosives, and then they’d set them out in the Delaware Bay,” Dykes said.

The former Wave Building is the only intact structure that still exists from the mine-building operation, but other foundations can be found in the immediate vicinity. Closer to the fishing pier is what’s left of an octagonal water flotation tank that was used to test the mines, Dykes said.

The Hawk Watch sits atop Battery Hunter, which was built to house two 6-inch guns.

Just to the south, the McBride Bathhouse at the state park’s main parking lot was literally built on top of the Panama mount for a 155-mm gun. There are four of those in the dune area near the bathhouse.

“These are some of the very first guns that came to Fort Miles,” Dykes said.

They’re called Panama mount guns because they were initially designed to defend the Panama Canal, Dykes said. She said these particular gun mounts offered mobility because they could turn to cover a wide range. While they couldn’t go 360 degrees, they could go pretty far, she said.

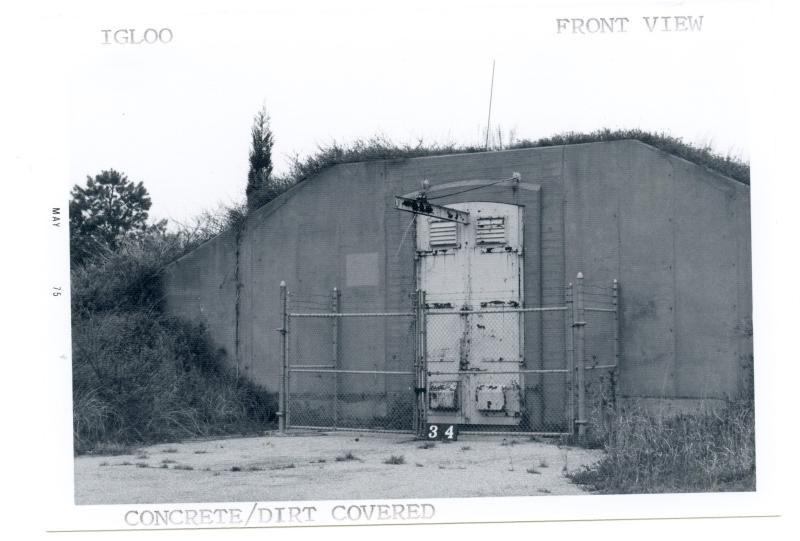

Along the bike path farther south are what park staff call igloos. They housed ammunition. Dykes also recently learned they stored TNT for the mines.

After visitors enter the park and head toward the campground, the remnants of a plotting station can be seen in the woods just off the road.

“That used to be the brain of the [operation],” said Melville, adding that the structure was where soldiers would calculate where to aim the fort’s artillery.

Underground structures

There are 16 underground structures in the park. Some are in the form of storage igloos, which can be found along the bike loop in the park. Melville said they were cleared out just in the last five years. He said some contained “mystery barrels,” which were simply leftover oil, transmission fluid and other maintenance-related materials. Today, some of the structures are used for storage, he said.

Some buildings are being used for the same purpose as they were 80 years ago. Near the park office, a building that housed vehicles does, in fact, still store cars. A maintenance building from the 1940s is still a maintenance building.

“The Army pretty much just cleared out and left everything,” Dykes said. “So every once in a while somebody will be like ‘Hey, I found this thing, and I think it’s original. Do you want it?’”

An example of history that’s not so obvious can be found along the Pinelands Trail. Melville said there are hills that may not appear to be natural, and that’s where rail revetments were located.

“The [rail] line would come in and split, and then there was a whole part of the line that went into what is now the Pinelands Trail for the 8-inch railway guns,” Dykes said. “There were four of them back there, and you can still see the horseshoe shape. It looks like a hill, but if you take a close look, you can see its shape, which is where the guns would’ve been sitting on the tracks pointed out at the Atlantic Ocean.”

The easiest access to the site is from the trailhead at Fort Miles, Dykes said.

On the way out the park, a two-story building now serves as a dorm, but it would have been used as housing for officers during the World War II era.

Editor’s note: Cape Henlopen State Park’s role in the Cold War and pre-World War II will be discussed in the second part of this story.

.jpg)

.jpg)