Local civil rights icon Doug Gibson celebrates 100 years

Born in the Eastern Shore town of Trappe, Md., in 1923, Doug Gibson refused to allow prejudice determine the course of his life.

As a Black man, he consistently reshaped boundaries created by society as he forged his way from the Great Depression to the celebration of his 100th birthday Feb. 28.

“The things I did were unheard of, and I had to be out of my mind to do some of them, but I came through all right,” he said in a slow and gravelly voice.

Seated on a couch in the Milford brick house he designed and built himself, Doug reminisced about his accomplishments, which he attributed to a natural desire to try something new.

“Anything that you really want to do is easy for you to do,” he said simply.

Doug’s father skippered a commercial schooner on the Chesapeake Bay and later became a sharecropper, growing corn, wheat and tomatoes while raising sheep, cattle, horses, chickens and pigs.

“I ain't nowhere near what he was,” Doug said. “He was a brave, honest, good man. He didn't back down from nothing or nobody.”

As a child, Doug rode in a horse and buggy, where bricks heated in a fire and wrapped in towels were placed on the floor to keep his feet warm. “I watched my mother do that many days,” he said.

Throughout his life, boating remained his favored pastime. “Anything to do with the water was my favorite,” he said. “Even as a young kid, I wanted to be a sailor.”

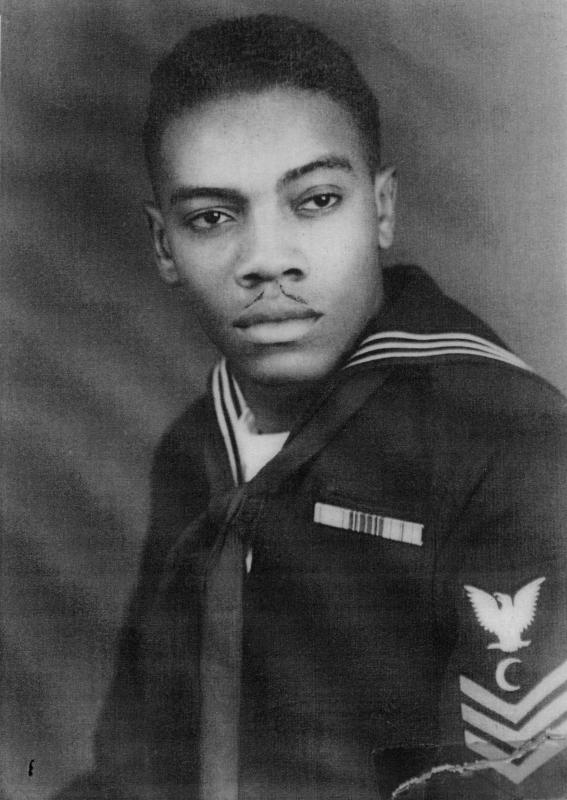

This affinity led to his 1941 enlistment in the Navy. “I enjoyed it, but I didn’t enjoy the segregation,” he said.

Doug was stationed in Pearl Harbor, where he oversaw the cafeteria for four years and had 25 sailors reporting to him. He ended his career as a petty officer second class.

“Every taxpayer should see Pearl Harbor because there’s so much armament there that most people don't know the United States has. Battleships could string from here to Dover,” he chuckled.

The base was not yet rebuilt when he served; wrecks, including the Arizona, were visible under the water. Trains carrying captured Japanese prisoners of war operated 24/7, he said, taking men to the northern part of the island to work in cane fields.

One day, he recalled, a truck carrying ammunition was backing out to load a plane for an air raid when a 200-pound bomb started to roll off the back. A sailor caught it and placed it back on the truck.

“The next day he couldn't pick it up,” Doug said. “If he hadn’t caught that I'd be wearing wings now.”

Another day, he served breakfast to seven sailors before they reported to work in the ammunition dump. Later, an explosion rocked the base and he never saw the men again.

“I can see that right now,” he mused. “It was a very dangerous place to be.”

The base wasn’t always hazardous. “In Honolulu one day – I hadn't seen nobody from home for years – we were going from one street to another and I walked up to a guy I lived right near and went to school with,” he said.

“We both stopped right in the middle of a train track. Men stopped the train,” he laughed. “We hadn't seen each other in years, but we were neighbors when we were kids. Can you imagine seeing somebody that far away from home? Everybody around us just gave us our way. Everything stopped so we could enjoy each other.”

Doug planned on staying in the Navy until the GI Bill was announced. He enrolled in Delaware State College, which at the time was at risk of closing. The influx of veterans helped keep the college afloat.

In the summer, he worked at the Tred Avon Yacht Club in Oxford, Md. It didn’t take long for the commodore to ask him to run the whole food and beverage operation, which he did for 20 years. Doug was renowned for his crab cakes; he still refuses to share the secret ingredients.

“Whoever heard of a Black person running a white yacht club?” he said. “Nobody, but that was me. I was good at what I did. I was always of the mind that if you're going to do something, be the best.”

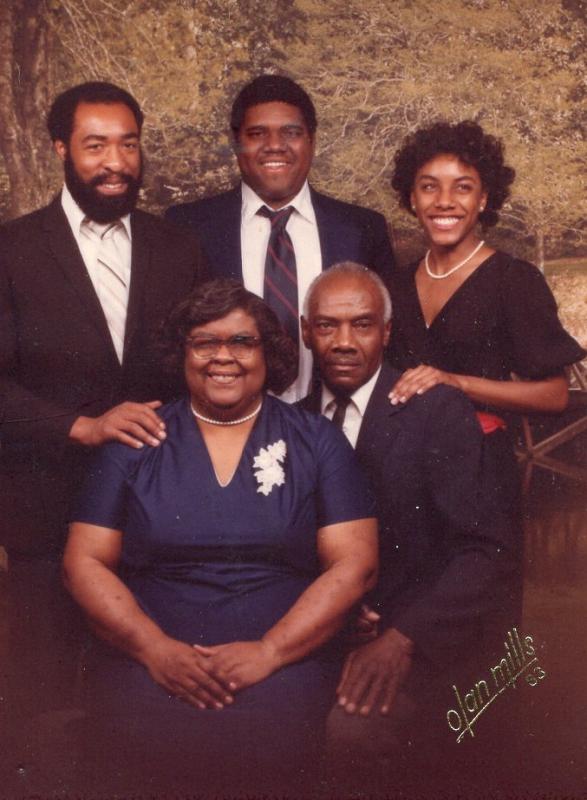

At Delaware State, Doug met his future wife of 51 years, Dorothy, and majored in industrial arts. He was an original member of the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity and graduated in 1950.

Later, he earned his master’s degree in school administration from the University of Delaware, where, he said, as a Black man, he could buy a sandwich in the cafeteria but had to go outside to eat it. While in Newark, he also earned his pilot’s license and flew Cessna single-engine planes.

One college project required him to design a home. Doug took the assignment further and built the home in 1961. He collected bricks from a fallen fireplace in a burned-down building, bought cement and practiced laying bricks in the backyard. He taught Dorothy how to lay the wood floor; she installed all the floors.

“It was fun building this house,” he said. “I had been dreaming of a brick house ever since I was in high school.”

Doug first taught industrial arts at Benjamin Banneker, then a Black school, before taking a position as an architectural engineering instructor at Delaware Technical Community College in Georgetown.

His son Darrald recalled the time Del Tech planned to have its Christmas party at Shawnee Country Club, which at the time did not allow Black members. Black teachers were upset the party would be held at a place they could not normally go, but were afraid to broach the topic at a meeting.

“But guess who stood up?” Darrald laughed. “And they changed it. One thing I will say about Dad is, he’s fearless. If he has fear, he doesn't show it at all.”

Doug chuckled. “Anything I saw wrong that I was denied admission to or something, I meant to destroy it, and I did. I didn't let nothing stop me, and it took a lot of guts to do it at the time.”

His determination led him to be the first African American to run for Milford Town Council, Darrald said.

“I was only 8,” Darrald said. “He was upset because there were things that needed to be done in the Black section of town that weren’t being done, and the other Black people in the community weren't willing to speak up about it. They had a white man who was in the council, but he wasn't really representing their needs, so dad decided he was going to run for office. This was back in 1963.”

The news made the front page of the Milford Chronicle.

“These two carloads of men pulled up in front of our house, about eight white men,” Darrald said. “And they began to yell, ‘Doug Gibson, come out! Doug Gibson, come out! We want to talk to you!’”

Doug grabbed him, Darrald said, and ushered him into another room, telling him to stay there no matter what. Of course, Darrald sneaked out to watch.

“I can't figure out what he's doing because instead of going to answer the door, he goes down to the basement,” Darrald said. “And now I'm really puzzled because he comes back up with a shotgun and I’m wondering, is he going hunting?”

“Dad let them have their say and then he said, ‘Now you men, you go back and you tell Isaac, because I know that's who sent you, if he got anything to say to me he needs to come here and tell me to my face and don’t send his bird dogs after me. Now get off my property!’ and they left.”

The men later called for a meeting with Doug. Before he left, Doug laid $300 on the table, telling Darrald and Dorothy they may need it for bail money. When Doug returned, he said the men realized they better get used to him, because he refused to back down or change.

“He was a one-man civil rights movement in Milford because he was the only one really willing to challenge the white hegemony at that time,” Darrald said.

While Doug wasn’t elected that year, the next year another Black man ran and won. Doug ran again and was elected in 1990.

Darrald said he remembered other Black people coming to the house to warn his mother to get Doug to stop or he was going to get killed. She was scared, Doug said.

“The whites were very demanding,” Doug said. “They knew nothing would happen to them if they did something, and I was determined to get done what I wanted to do.”

“It took guts to do it, and at that time I had that,” he smiled. “Being Black was a very very dangerous thing to be only if you spoke up for yourself. You weren't supposed to do that. You were supposed to take whatever was thrown at you and say nothing.”

Darrald said while in college, he told a girl he was dating about his dad and his accomplishments. “She thought I was lying because no one man could do all those things,” he laughed.

“She didn’t know me,” Doug interjected, chuckling.

“Growing up with him as a father,” Darrald continued, “and my mom was no slouch either, I did not understand that I was a second-class citizen. When you see your dad tell eight men they’re bird dogs and ‘get off my property’ and they walk away, what do you think?”

“I was supposed to have been shot,” Doug said. “I wasn't supposed to be so brave talking to white people that way. I had nothing to be afraid of.”

Doug shared his talents in architecture, farming and fishing with the community. He designed several churches throughout Delaware free of charge, as well as the Delaware Agricultural Museum and the Square Club, a social club in Dover.

In his backyard garden, he raised chickens and crops, and took the excess to people who were struggling, Darrald said, same with the extra fish he caught. “He always shared what he had with those who needed it.”

Doug’s father was a hunter who made his own decoys with a hatchet and knife. He recalls going to a Ward Brothers duck-carving show and decided to carve his own ducks.

In fact, Doug became an internationally recognized artist who was invited to demonstrate the craft at the Smithsonian in 2003. A collection of his work is on permanent display at Delaware State University, and his ducks are now in homes all over the world.

“One thing,” Darrald said, “despite all the things he’s done, if you listen and look closely, he never really left that [childhood] farm. All the things he did on that farm he still does to this today.

“Well, he has slowed down,” Darrald chuckled. “He started slowing down when he was 95. He last gardened when he was 97.”

“I enjoyed it,” Doug said. “I enjoyed seeing things grow because of what I did. I never wanted to be nobody's employee. I wanted to do everything on my own.”