As wind power technology develops, wind turbines reflect the changes. But unlike computers, which keep getting smaller, wind turbines are getting taller and producing far more power.

Take the Gamesa G90 turbine at the University of Delaware’s College of Earth, Ocean & Environment in Lewes. Installed in 2010, the turbine stands about 400 feet high when its 140-foot-long blades are at apex height. It produces 2 megawatts of power, which, according to the turbine website, is enough to power the campus’ six buildings.

Ten years and many generations of turbines later, General Electric recently announced it had completed construction of the first nacelle – the head of the turbine – for the 853-foot-tall Haliade-X. This turbine, with 351-foot-long blades, is marketed as the industry’s first 12 megawatt producing turbine. It is expected to be ready for commercial production in 2021.

This information is relevant to the Cape Region because in 2017 the Maryland Public Service Commission awarded offshore wind renewable energy credits for two wind farm projects.

The larger of the two, U.S. Wind Inc., is expected to be built off the coast of Ocean City, Md., and calls for up to 32 turbines to produce 268 megawatts a year – which, according to U.S. Wind Inc., is enough energy to power 76,000 homes.

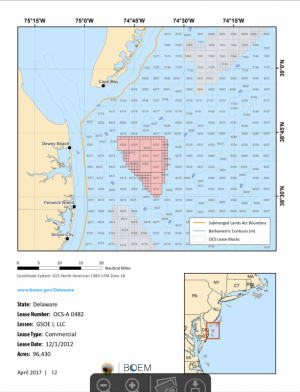

The second project, Skipjack Wind Farm, is off Delaware’s coastline. The Maryland commission approved a 15-turbine, 120-megawatt-producing wind farm – enough energy to power about 35,000 homes. U.S.-based Deepwater Wind, which built the country’s first operational wind farm off Block Island, R.I., won approval for the project, but, in late 2018, the company was bought by Danish-based Orsted.

The five turbines that make up the Block Island project are manufactured by General Electric, but with thousands of turbines in seas across the world, Siemens Gamesa is a global competitor.

Steve Dayney, head of Offshore North America for Siemens Gamesa, said Siemens Gamesa has 3,000 machines globally, producing 13,000 megawatts of power.

Speaking by phone during a business trip in Europe, Dayney said a combination of things have led to larger turbines. He said technology continues to get more sophisticated and more reliable, which allows for bigger components and greater efficiencies. He said competition is also a driving force.

“Competition leads to the improvement of any product,” he said, declining to get into specifics because of proprietary information.

Dayney, who has been in the wind business since the mid-1990s, said he’s astounded by the progress that’s been made. He said in 2001, the thesis for his master’s degree was about turbine technology in the United States versus Europe. He studied a turbine in Sweden that produced 1 megawatt of power and had blades 130 feet long.

“It’s remarkable how much the technology has changed,” he said.

Dayney said the East Coast of North America is a great place for wind farms noting there’s a constant source of wind that blows at a fairly high speed and, because the continential shelf extends for hundreds of miles, the water is relatively shallow.

Siemens Gamesa currently has no turbines in North America, but Dayney said the company is scheduled to start construction next year off the coast of Virginia, near Norfolk. He said as wind farms begin to come online they will spark significant involvement from community stakeholders – elected officials, residents and business owners.

That’s where people like Aaron Russell come into play. Russell is a PhD student in the Water Science and Policy program at the University of Delaware. He has a master’s degree in geography and environmental studies. He’s a social scientist interested in how energy system transformations affect local communities.

Russell surveyed the people of Block Island to find out how they felt about the wind farm off the coast. He said for the most part, support for green technology was fairly strong; respondents were happy to no longer be using diesel fuel as the island’s energy source, and there was a feeling that the wind farm showed progress toward a green energy future.

Still, not all respondents offered glowing reviews. Russell said some respondents didn’t like losing the uncluttered horizon line, being able to stare at nothing but the sea, he said.

A lot of coastal towns in New England have islands and lighthouses off their coasts, already blocking the horizon line, while here in Delaware, it's empty ocean and slow moving container vessels as far as the eye can see.

Russell said it’s difficult to directly compare Delaware and Rhode Island because of the physical features – and because the projects are very different. Rhode Island is a relatively small pilot project, he said, which is very close to shore, especially to Block Island. An offshore wind project near Delaware shores, as designed, is composed of more and larger turbines placed much farther out.

Russell said larger turbines means it will take fewer of them to produce the same amount of power. He said they’re also constructed much further apart, which means they won’t dominate one specific area.

Typically, Russell said, 8- to 10-megawatt turbines are the size of the ones companies installed. He said 12-megawatt turbines are marketed for Asia and Europe where the offshore turbine industry is much further developed.

Turbine technology may continue to improve, but Dayney said there are big challenges in the North America market. He said it will take time to build the necessary infrastructure and educate a workforce. Nearly as important, he said, is getting communities comfortable with turbines.

Russell wholeheartedly agreed. Developers need to be in the community early and often, he said.

Looking to the future, Dayney said there’s a significant market for wind power in North America, estimating that by 2030, turbines will produce 15,000 megawatts of power, versus the 30 megawatts produced now at Block Island.

Dayney said he thinks turbines will continue to increase in size, but he declined to say by how much.

“Twelve years ago, I predicted turbines were at maximum size. That was proven wrong very quickly,” he said.

Skipjack Wind Farm

Unlike advancements in turbine technology, wind farms take much longer to come to fruition. Since being announced in 2017, there have been a number big advancements to the Skipjack Wind Farm project, but there are still no turbines in the water.

First, in October 2018, Deepwater Wind, the American company who won the right to build the wind farm, was bought by the Danish wind power company Ørsted for over $500 million.

Second, in July, Tradepoint Atlantic, a 3,300-acre global logistics center in Baltimore County, Md., announced an agreement with Ørsted U.S. Offshore Wind to develop Maryland’s first offshore wind energy staging center. The company plans to invest approximately $200 million in Maryland.

Most recently, earlier this month, Ørsted announced a proposal to build a facility in Fenwick Island State Park that would allow them to connect to the power grid. In return for the state allowing the construction of the facility, Ørsted is willing to make approximately $15 million worth of improvements to the state park. Those improvements include a two-story parking structure, a Route 1 pedestrian crossover connecting the bay and the ocean, an outdoor amphitheater, housing for lifeguards, a new park bathhouse, a new building for the Bethany-Fenwick Area Chamber of Commerce and an overall improvement in roadway infrastructure. The state is still taking comments on Ørsted’s proposal. Comments can be made at www.destateparks.com/fenwickimprovements.

In an Oct. 2 email, Joy Weber, Ørsted's development manager for the Skipjack Wind project, said Ørsted submitted its Construction and Operations Permit to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management in April 2019. Pending obtaining necessary permits and approvals, she said, Ørsted anticipates construction beginning in 2021, with commercial operation slated to begin in late 2022.