For some men, evil is an opportunity to act out their prejudice and thereafter profit from it. Bryant W. Bowles (1920-97) was one of those men. But he needed the right place and the right time. Events in mid-century Delaware provided both.

By the early 1950s, voluntary desegregation practices slowly emerged in a few Wilmington-area hotels and some downtown movie theaters. Then there were Louis Redding’s NAACP legal victories in Parker v. University of Delaware (1950), Belton v. Gebhart (1952), and Bulah v. Gebhart (1952) – all school desegregation rulings rendered by Chancery Judge Collins Seitz. In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Warren Court affirmed Judge Seitz’s Gebhart rulings and returned them to Delaware authorities to implement (the Parker case was not appealed).

It was all a good omen, but would it be realized? Bryant Bowles hoped not. He entered the post-Brown picture to derail the integration of Delaware schools. Though perpetually on the run from the police, creditors and the employees he cheated, he was nonetheless a venturesome grifter. To that end, when he drifted into Delaware, he donned a new title: president of the National Association for the Advancement of White People. There was money in bigotry. Segregationists knew him as the “$5 man,” owing to the bounty of monies he routinely collected to advance his cause and fill his pockets.

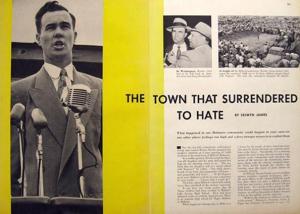

With masterly skills, in 1954, Bowles fired up crowds to oppose school integration. His racist campaign went into full gear just as Milford schools began to admit Black students. Big banners reading “Stay Out of School” and “Kick ‘Em Out” appeared as part of an effort to urge the parents of white students to have their kids remain out of school. It worked: “Only 456 of a total of 1,562 students turned up at the reopened Lakeview Avenue School.” To up the racist ante, a wooden cross was set on fire in a field opposite Milford High School. While Bowles might not have directed that action, he certainly was its proximate cause. By his race-baiting measure, that was a badge of honor.

Things got worse: “The town [of Milford drew] international headlines as angry whites organized picket lines outside the schools and through acts of intimidation induced officials to withdraw Black children” despite the school board’s previous plan to commence integration. The counteroffensive was on and gained momentum.

With Confederate-like opposition to federal and state attempts to implement Brown’s promise, Bowles promoted “local control over local affairs.” The “$5 man” also orchestrated an effort to take segregationist control of local school boards. The Supreme Court be damned: “The people are the boss,” he declared. He worked “for them,” those who opposed Brown’s ruling. Of course, his grifter psyche realized the monetary gain to be acquired from such disingenuous promises.

Bowles had collaborators to galvanize his racial combat campaign. There were, for example, evangelist preachers such as local Revs. Claude Lynch and Fred Whitman, the latter who claimed that “scripture demanded racial separation and, in a creative interpretation of the Bill of Rights, asked the government to grant them separate schools as a matter of freedom of religion.” Charles P. West, the vice president of the NAAWP (later he was a representative in the Delaware House between 1997-2003), echoed that sentiment: “‘[I]f God had intended us to associate with the colored race ... he wouldn’ta made n***ers. He woulda made us all white.’” Support also came from out-of-state figures in the person of Florida Sheriff Willis McCall, infamous for his 1951 shooting of two Black criminal suspects while transporting them for a new trial. McCall, a strong segregationist, zealously enforced anti-miscegenation laws as well.

Bowles’ populist campaign managed to intimidate some school officials, which allowed their vacancies to be filled by five well-known businessmen, all segregationists. In no time, they reversed things and voted to resegregate the schools. Black students were removed and reassigned to all-Black schools. Jubilant, 2,000 NAAWP supporters held a victory party. The celebratory spirit was short-lived once NAACP lawyer Louis Redding petitioned Judge William Marvel to intervene, who then ordered that the Black students be reinstated. The Delaware Supreme Court, per Chief Justice Clarence A. Sutherland, reversed that temporary ruling. By February of the following year, Sutherland shifted gears, but only a bit. While local boards might elect to admit Blacks, he also stressed that “[s]tates ... are not required, at the moment, to desegregate their schools.” In other words, meaningful remedial justice was delayed.

As for Bryant Bowles, time and truth began to catch up with him. On Oct. 8, 1954, Delaware attorney Albert W. Young moved to revoke the NAAWP charter for its fraudulent practices. As Clive Webb’s research has revealed, Young also accused Bowles and the NAAWP of “attempting ‘by means of mass hysteria, mob rule, boycott and dissemination of race prejudice,’ not only to intimidate Black families and school officials, but also to encourage white parents to violate school attendance laws.” Two days later, and pursuant to a demand from Gov. Caleb J. Boggs, Bowles was arrested. He was taken into custody and thereafter arraigned in courts in both Kent and Sussex counties. The combined bond was $6,000.

What followed was playbook Bowles. The demagogue ventured to “Harrington Air Field for a sundown rally at which he announced, to the cheers of 5,000 supporters, the death of Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson.” Soon enough, however, his rebel gesture was no more than a case of pride before the fall. A Dec. 11, 1954 Associated Press story began this way: “Bryant W. Bowles ... faces two charges of conspiring to break the school laws when the court of Common Pleas convenes ... Judge A. B. Magee will hear arguments on a motion to drop charges against Bowles, represented by attorney Everett J. Warrington and Daniel J. Layton of Georgetown.” Of course, where exactly Bowles got the money to pay these two well-known lawyers was the question. (Layton was the chief justice of the Delaware Supreme Court between 1933-45. His father, Congressman Caleb R. Layton, voted against proposed federal laws to outlaw racial lynching.)

Luck and prejudice favored Bowles ... up to a point. A jury found him not guilty. When law officials continued to track him, and after the cash flow ended, he moved to an area near Beaumont, Texas. There he used a shotgun to kill his brother-in-law in May 1958. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to life. Bowles appealed, but to no avail. Fifteen years later, he was paroled. Up until 1997 when he died of congestive heart failure in Tampa, Bowles had run-ins with the law over drug trafficking.

To give the devil his due, Bryant Bowles could claim credit for launching one of the first resistance campaigns to thwart school integration. It would take considerable time to undo the evils he unleashed. To do that, courageous students, activists, people of faith, politicians, along with lawyers and judges had to unite to combat the evils that Bowles and his like perpetuated.