In a small, dimly lit laboratory on the campus of the University of Delaware's College of Earth, Ocean and Environment, researchers are learning how corals and anemones adapt to changing ocean conditions.

By ever-so-slightly changing the acidity and temperature of sea water in tanks containing anemones, researchers are using ecogenetics to study if and how the genetic traits of corals and anemones adapt as environmental conditions change, said Tom Hawkins, a doctor of marine ecophysiology.

The research is important, as coral reefs around the world are disappearing at an alarming rate, which scientists say is a partly a result of climate change and an acidification of ocean water.

“It's quite a big problem. It's about as big a problem as you can imagine,” Hawkins said. “The oceans are more acidic now than they have been for several million years.”

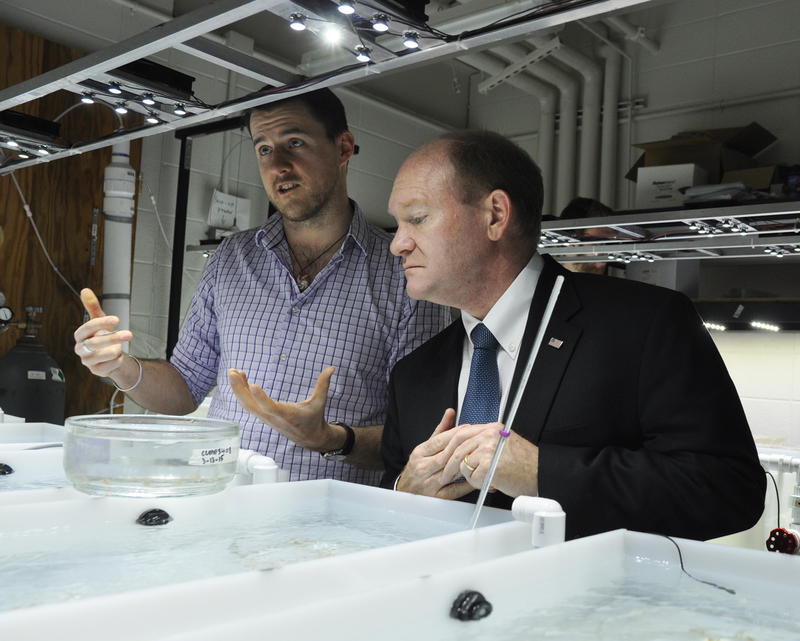

During a recent visit to the lab, Delaware U.S. Sen. Chris Coons commented on his personal experience with vanishing coral reefs off the coast of St. John in the Virgin Islands.

“My children have been going there for a decade, and they were bemoaning the fact that it's painfully obvious that the corals are collapsing,” he said.

Hawkins said most of the loss of coral ecosystems can be attributed to localized development near reefs, and it will only get worse in the future.

That is not the case in St. John, as the coral reefs are in an area mostly protected by a national park, meaning the deterioration of the ecosystem is unlikely to have been caused by human activities along the coast.

“What's striking to me is on an island like St. John … you can see it moving fast,” Coons said.

Ocean acidification is a major problem, Hawkins said, and will likely result in the loss of many reefs around the world.

Hawkins, ecogenetics expert Adam Marsh and UD researchers are studying anemones because they have very similar biology to corals. In both cases, the organism hosts algae in its body. The algae harvests sunlight with dissolving carbon dioxide and turns it into sugar, which is available to the organism. In the case of coral, the sugar is what gives the organism so much energy and power to build large-scale coral reefs.

Because of the soft and squishy structure of anemones, Hawkins said, they are easier to work with in a lab setting. The limestone skeletal structure of coral is more difficult, he said.

“They're really sensitive, whereas anemones are very much the lab rat of this kind of biology,” he said.

In both corals and anemones, asexual reproduction is common, meaning fragment pieces of the organism bud off to create a new coral or anemone. UD researchers are looking at these offspring to see if genetic modifications are being passed on from previous generations, which would show the organism is adapting to the new environment.

“The novel thing is a lot of studies and a lot of other institutions have looked at coral adaption, but they haven't focused on specific mechanisms. That's what we're doing,” Hawkins said.